The Bibliophile: The Unyielding Human Voice

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

A few notes from John Metcalf, followed by a Biblioasis interview with Elise Levine, author of Big of You

When I happened upon Elise Levine’s stories in 1994 or thereabouts I was editing for Porcupine’s Quill press. What struck me about even her earliest work—and I do mean ‘struck’—was how polished and sophisticated it was; she was aeons ahead of her contemporaries having been reading Beckett at the age of fifteen.

“In his works I find a means with which to capture the psychic and emotional states of betweenness, constraint, defiance, the craft involved in giving shape to the tension between the abjection of self-exile and the unyielding human voice. I grasp how what is not said on the page can speak volumes: how silence itself can render an eloquent and moving subtext, and wrenchingly convey the unspeakable” (Elise Levine, Off the Record, Biblioasis 2023).

She refers more than once—though not directly—to Beckett’s play Not I (1973), a play in which Billie Whitelaw was shrouded entirely in black cloth with only her mouth illuminated—and the spotlit mouth delivered at tumbling speed a flooding monologue. This is the way I hear Elise’s fictions; her stories can be described as instruments performing a voice. She has no patience for plot, for ‘what happens next’; her stories are intricate solos; she wants us not to think but to listen; she demands our surrender to the performance.

John Metcalf

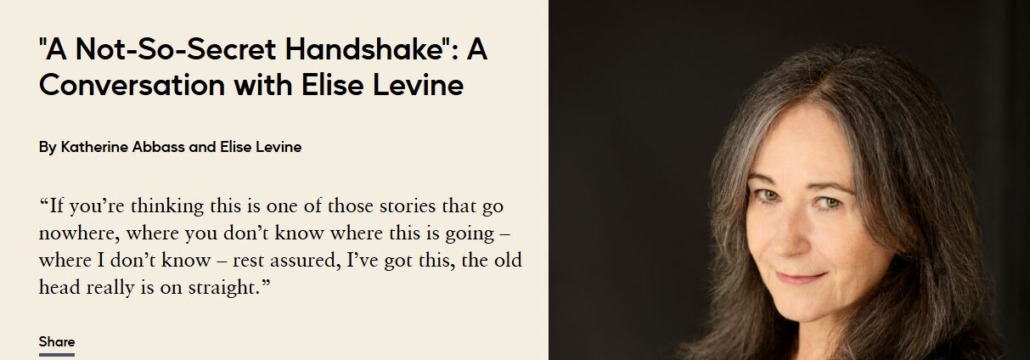

A Biblioasis Interview with Elise Levine

DB: Big of You was my introduction to your work. I loved it so much, I’ve been working my way backwards through your catalogue. I’m curious to know how you see Big of You as being different, or a shift away, from your previous books.

EL: Thank you for the love! Big of You extends what I’ve done in previous books, in which I’ve explored questions about power and voiced-over lives and defiance. I carried these concerns with me in writing Big of You, but I also saw it from the outset as more focused than my first two story collections and at times lighter in tone and more sardonic than my novels and novellas. This book full-on centers ambition, striving, the puncturing of expectations, the capacity for self-deceit, and the delight in potentialities and capabilities. Before I began writing the stories in Big of You, I saw it having a clear overall architecture: I would braid the stories together by linking some of the characters through paired narratives in which the characters appear at different points of their lives or otherwise intersect with the situations and preoccupations of other characters. I knew too, before I began writing any of the stories, that I would lean heavily on fabulist or surreal elements to capture lives lived—or entertaining the possibility of living—beyond imposed expectations, and that these elements would help get at the strange internal weather and sea changes over time that personhood can entail.

Big of You strikes me as primarily character-driven. It’s also very attentive to language, but I imagine largely as a means of representing the peculiarities of character (correct me if I’m wrong). What is it about character that appeals to you? How do you discover and approach a new character? Do you ever find the seeds of character in your own life?

I’ve always been a character-driven writer, and yes, I use language—foregrounding it, even—fully in service of evoking character, because in character lies the Big Question: we have these single lifetimes—as far as I know—and what do we do with them? In view of the dark door of individual extinction we all must pass through. And the possibility, that continues to rapidly feel more pressing, of the extinction of humans as a species, along with every other living thing on this planet. My initial ideas for character strike out of the blue and then I spend time in what I think of as a pre-writing stage: writing partial scenes, especially the opening and endings, and making notes on who the characters might be, what their situation is. Fully developing the character, their story, typically takes me a scandalous amount of time and a crazy number of drafts in which I keep digging deeper, further in, asking what does this character really want, what do they fear? Sometimes characters do initially lift from my own life. I mean, I was once a teenage girl let loose for a summer in Europe, as in the story “Arnhem,” which opens the book. I once lived in an apartment in which the living room was dominated—menaced?—by a baby grand piano, as in “Penetrating Wind Over Open Lake.” But with both of these stories, as was the case with others in which I borrowed details from my own life, when I began writing them in earnest the narratives soon wildly diverged from my personal histories and took on their own beast lives.

One of my favourite stories in Big of You is the three-part “Cooler.” For those who haven’t read it yet, the first part follows a sad-sack casino worker, the second an isolated spacecraft, and the third part features a grumpy, supernatural creature with a blue tail (these short descriptions really don’t do the story justice). The three sections are wildly different in tone. In a recent interview with The Ex-Puritan, you explain that the story arose from an interest in the concept of “coolness” and how what’s cool might be variously depicted. I love that, and wonder if any of the other stories in Big of You began in distinct ways (even if not necessarily derived from a concept)?

Yes, each of the other stories in the book did begin in distinct ways, but usually with a strong sense of character and situation, and a sense of voice and form. For example, I knew from the outset that for “Return to Forever,” which is about three older women who vacation together in the desert at Joshua Tree, while a fourth friend remains back home in a memory-card ward, I would use the first-person-plural point of view and sweeping, single-paragraph sections to evoke a communal voice. In “Witch Well,” the final story, I knew I wanted, before I even began writing it, to use a heightened fabulist approach and a kind of Stepford Wives vibe—along with a tone of perky defiance—to portray a woman’s grief and confusions over a profound loss against a backdrop of the seductive erasures of affluence.

I mentioned that “Cooler” is one of my favourites in the collection. Do you have a favourite story, or perhaps a character that you still think about with fondness or a sense of kinship?

I do feel a weird tenderness toward the main character in “Once Then Suddenly Later,” Adrien Tournachon, a nineteenth-century historical figure whose older brother, Gaspard-Félix Tournachon—better known by his pseudonym Nadar—is a central figure in the history of early modernity. He was a noted proponent of heavier-than-air flight—which led to the development of airplanes—which he advocated for through a series of catastrophic balloon flights. Along the way he invented aerial photography and air mail and underground photography, and was celebrated for his vivid, individualistic photographic portraits of luminaries such as George Sand, Victor Hugo, and Sarah Bernhardt. But his younger brother, Adrien, my main character, suffers from living in the shadow of his older and successful brother. My character is his own worst enemy: he drinks and squanders his time and lesser talents, at one point steals his famous older brother’s identity, lies about his own whereabouts and stature, and never fails to wallow in bitter self-pity. I don’t feel kinship with him, but I do feel for him: he stands in for the perils of striving to lead an artistic, creative life.

You’ve been a professor for a while now, and you teach in the program at Johns Hopkins University. How do you think teaching writing has influenced your own work?

Teaching fosters the excellent practice of generosity as a reader: it keeps me reading closely, open to a multiplicity of stylistic and formal approaches, and with an admiration and respect for other writers’ willingness to explore the infinite ways of what it means to be human. All of which keeps the creative wheels spinning in terms of my own work. Beyond a doubt, it’s a generative circuit, teaching writing and writing.

Have you read anything lately that you’d like to recommend?

Well, a ton of books! But I’ll try to keep myself decent and mention just a few. The story collections Other Worlds by André Alexis and Hellions by Julia Elliott: both are great examples of using fabulist elements to explore the shifts and surprises of selfhood, and both use language and form in innovative ways. Two Booker-longlisted novels: Audition by Katie Kitamura and Flesh by David Szalay, both of whose previous books I’ve loved. In these latest by Kitamura and Szalay, each very distinct from the other, language and form are nearly electric, and used to pose questions about hairpin twists and turns of identity. Another novel, The Passenger Seat by Vijay Khurana, I admired for its brilliantly controlled sentences and pacing, its taut and suspenseful narrative and vivid interiority—and its ability to generate tremendous empathy, despite the moral horrors it depicts. I also recommend two poetry collections, also quite different from each other: New and Collected Hell by Shane McCrae and Little Mercy by Robin Walter. Both books possess tremendous formal clarity and a just-go-for-it approach to digging deep into what it means to be conscious in this strange world we inhabit, for better or for worse. I habitually read a lot of books in translation and I’ll mention here just one of my favourites (okay, it’s actually a two-fer): On the Calculation of Volume (Books I and II), part of a seven-novel series by Solvej Balle, translated into English from Danish by Barbara J. Haveland. These first two in the series offer a lovely, surreal portrait of a woman experiencing suspended time, and uses a circumspect, minimalist tone and style—which achieves a nearly hallucinatory quality through its ultra-grounded and slow-paced approach to revealing the beauty and constancy of the many ordinary details of existence. I can’t wait for the remaining books in the series to come out in translation.

In good publicity news:

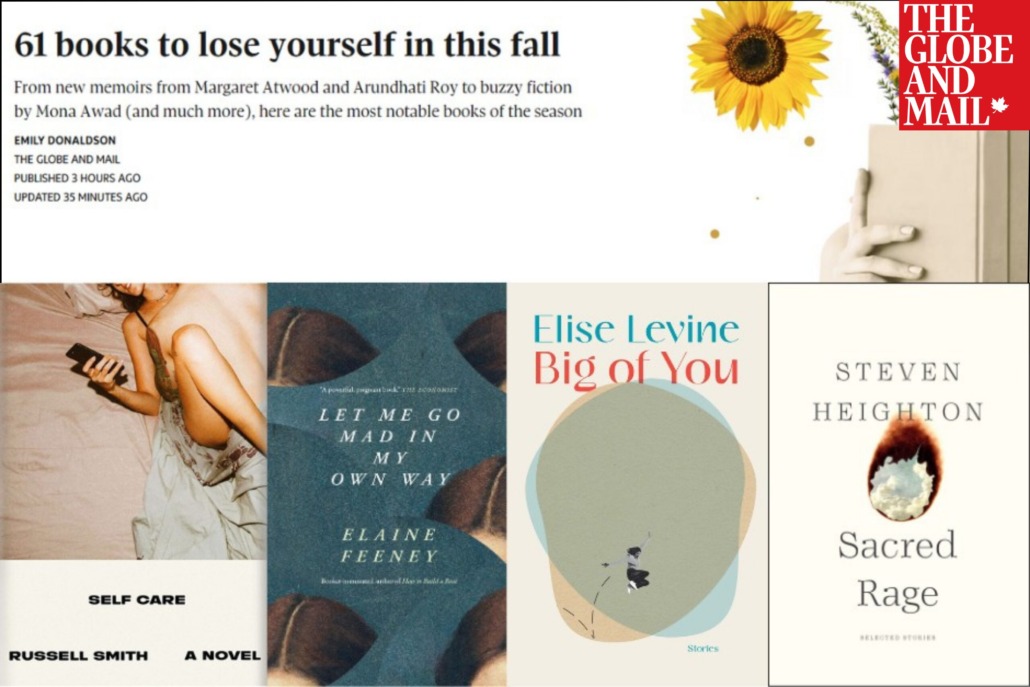

- Four Biblioasis books made the Globe and Mail’s list of “61 books to lose yourself in this fall”:

- Self Care by Russell Smith: “Smith is still at it in this story of a female journalist whose relationship with a man she’s ostensibly interviewing for an article on incel culture starts crossing into risky sexual and emotional territory.”

- Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way by Elaine Feeney: “The Irish author’s follow-up to the Booker-nominated How to Build a Boat involves a woman who [returns home] in the wake of her mother’s death and her father’s cancer diagnosis.”

- Big of You by Elise Levine: “Reading the still criminally underappreciated Levine is a visceral experience that seems to demand engagement of all one’s senses.”

- Sacred Rage: Selected Stories by Steven Heighton: “[Heighton] believed the short story was his greatest contribution to literature. For this collection, [his editor] Metcalf assembled 15 of what he deems the author’s best.”

- Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet was reviewed in the Daily Mail and on FictionFan’s Book Review Blog:

- Daily Mail: “A furtive, cagey novel reminiscent of Macrae’s Booker-shortlisted gem, His Bloody Project . . . In recounting one murder, Macrae subtly introduces the idea of another to produce a consummate slice of alternative true crime.”

- FictionFan’s Book Review blog: “Burnet’s writing is wonderful, as always, and diving deeply into complex characters is one of his great strengths . . . Highly recommended.”

- Russell Smith was interviewed about Self Care on The Commentary podcast.

- Marcello Di Cintio was interviewed about Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers on the Collisions YYC podcast: “From farms to care homes, Marcello illuminates a hard truth: we rely on foreign labour to survive, yet deny these workers a place to truly belong.”

- Illustrations from Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories 2025 were featured in the LRC Bookworm.

- Dark Like Under by Alice Chadwick was reviewed in Necessary Fiction: “Chadwick’s prose is rich and poetic, containing surprising images and gorgeous complexities . . . leaving the reader hungry to see what the author will do next.”