The Bibliophile: In Memoriam: Elaine Dewar (1948–2025)

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

On the Death of a Happy Warrior for the Public Good

I was walking into work the last week of August when Elaine Dewar called. She had just got back from holidays at a cottage with her daughters and grandchildren. I was waiting on the last round of edits for her new book, Growing Up Oblivious. But she was calling with much more dire news. She’d developed a pain on vacation, thought it might be gallstones or appendicitis, so went to emergency to get it checked out. They’d done a scan and it was cancer. There was no word on the origin or the extent of it yet, but she’d asked to see the ultrasound and had spent far too much time over her life as a science researcher looking at medical records not to know that it was almost certainly terminal. She hoped she’d have six months. She wanted to talk about the book. I demurred, said we didn’t need to now, that she had other things to worry about. But Elaine wasn’t having any of it. “Of course I’m going to worry about it, honey,” she told me gently. “It’s my last book, and it’s with you. So what are we going to do about this?” And with that, we got to work.

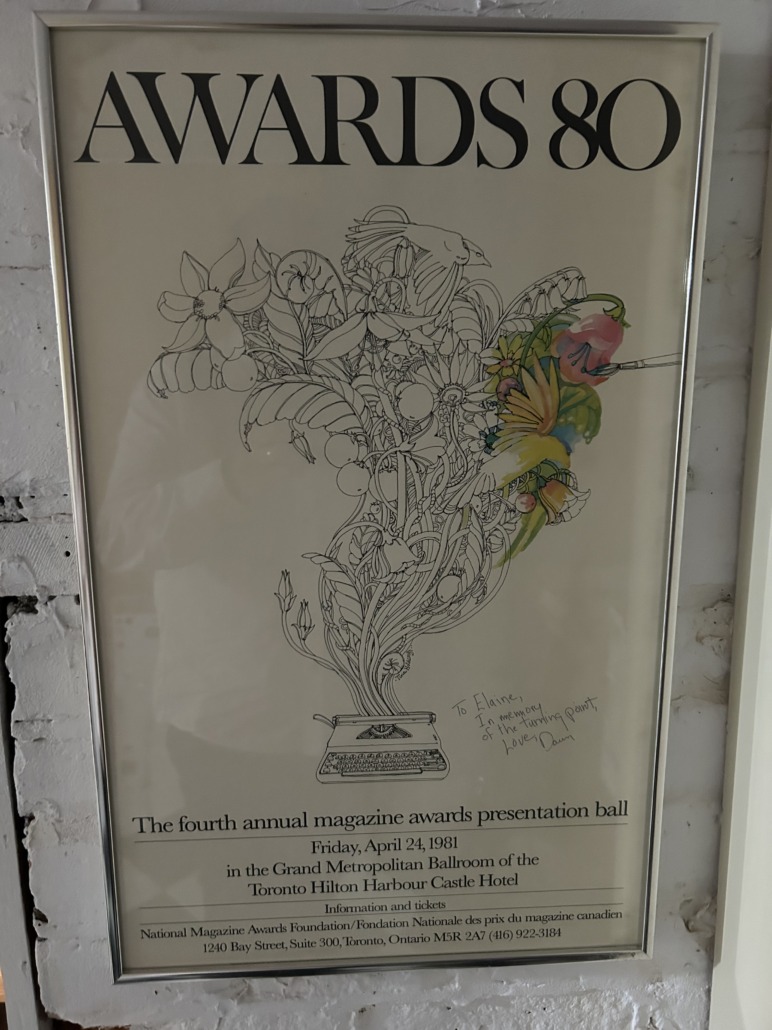

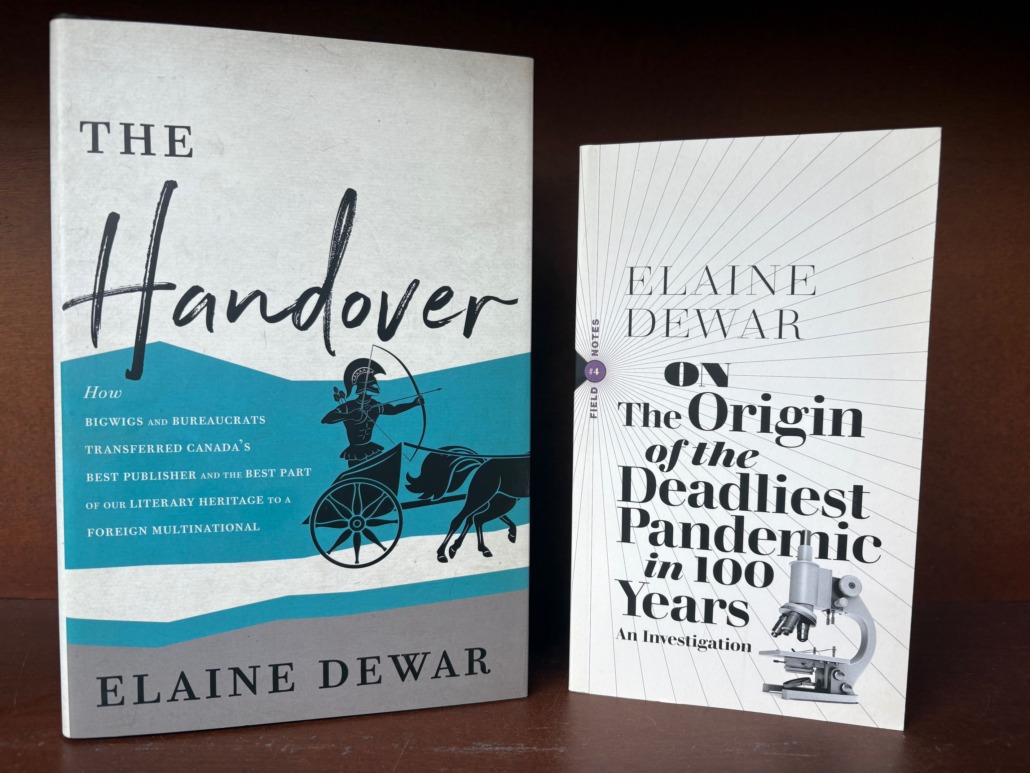

When Sam Hiyate wrote to me in early December 2015 with a proposal for Elaine Dewar’s book The Handover, about the sale of Canadian publisher McClelland and Stewart to Random House in contravention of Canada’s cultural protection laws, I knew little about Elaine’s work or reputation. Nor was this book, a work of deeply-researched nonfiction, our usual fare at the time; Biblioasis was much more strictly a literary enterprise in those years, borne forward by the ignorant hubris necessary to lay claim to such a designation. How else to continue in a world, even a small, purportedly literary enclave of the same, which cares so little about what we do? Our list in 2015—it strikes me now, at a time that one year pushes into another with almost no distinction, that 2015 was our break-out as a publisher, with three Giller nominations, a Writers’ Trust shortlisting, and a GG win, among other accolades: perhaps we wouldn’t have been sent Elaine’s proposal if that hadn’t been the case—was almost exclusively fiction, poetry, and works in translation; our only experience with nonfiction was literary criticism, with a sideline of regional history and more commercial titles to try and pay the bills. Reading Elaine’s proposal, I was worried that we didn’t have the publishing chops to pull it off. I knew that we didn’t have the money to properly fund its writing: I don’t think we’d ever paid an advance of more than a couple thousand dollars at that point. But we thought Elaine’s was an important story, so I pushed my envelope and offered $4000, which seemed a big risk for a press consistently skirting insolvency, and was able to swing her an additional $3500 in Writer’s Reserve funding. And for that Elaine produced what Jack Stoddart justifiably claimed to be “the single most important book about Canadian publishing . . . published in fifty years.” It garnered her a Governor General’s Award nomination and reams of press coverage, and resulted in a range of important conversations among anyone who cared about publishing or culture in Canada. It’s probably no surprise to those who knew her that it garnered Biblioasis’s first serious threat of a lawsuit, by a former Minister of Culture who had signed off on the sale of M&S, though when they learned that Elaine had dug up government documents that showed exactly what Elaine had claimed, this person (& their lawyer) thankfully never again darkened my inbox.

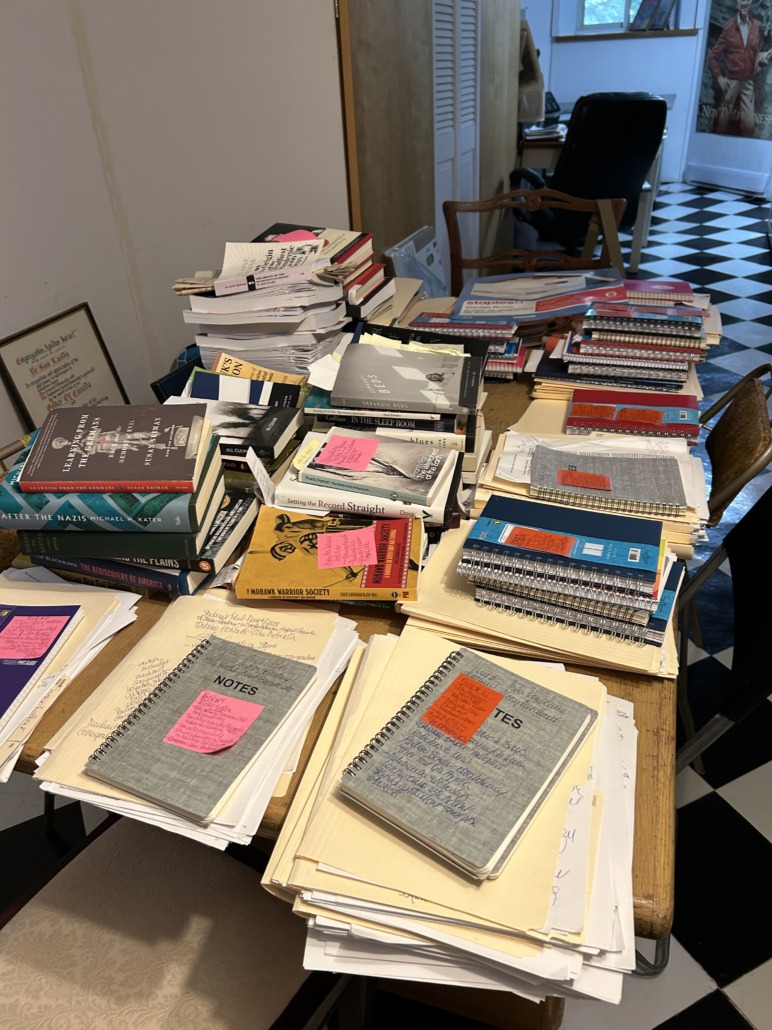

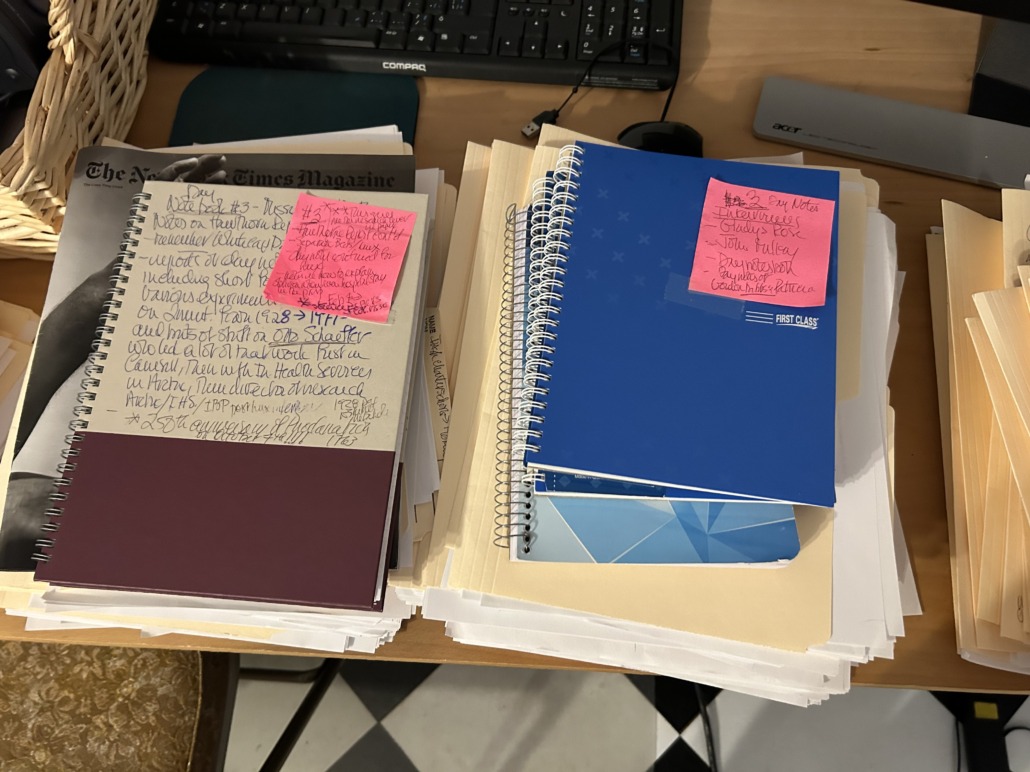

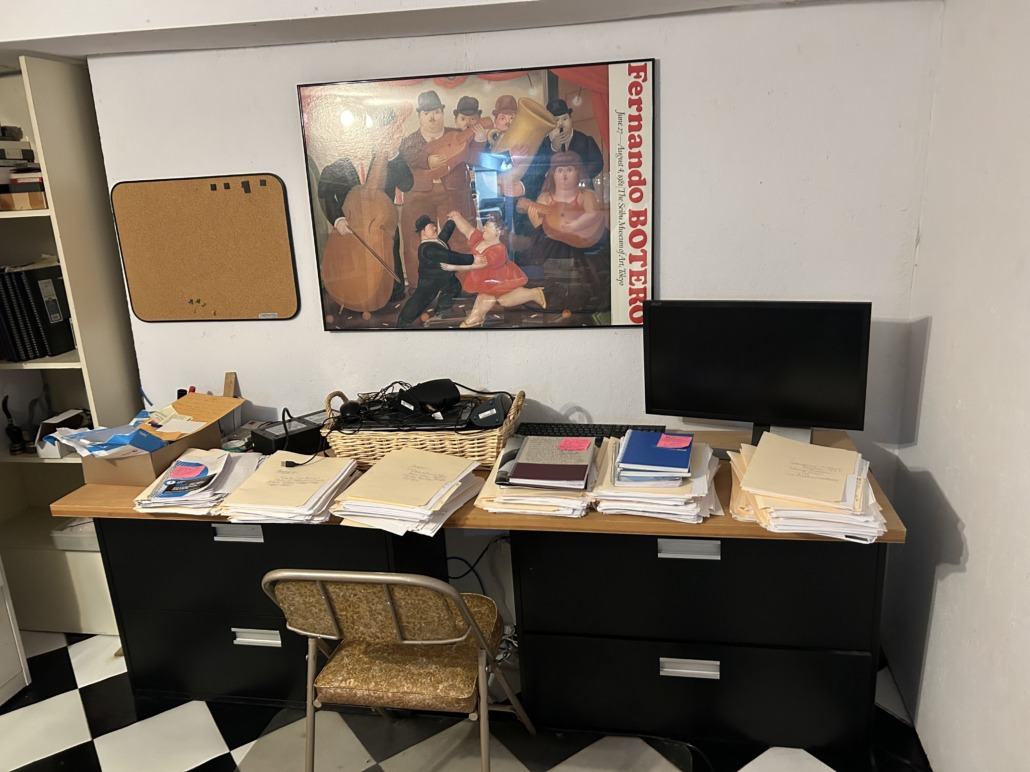

Because that was the thing about Elaine: she always had the receipts. There were times earlier in our working history that I doubted her claims, but I quickly learned that she always had the proof somewhere in a manila file folder on one of the multiple desks in her sprawling basement office; there was always a footnote. She taught me to read those footnotes with care as I read her manuscripts. She was a meticulous researcher, with a tenacity I’ve yet to see in another. Though she described herself, earlier this week, as being as “spiritual as an old sock,” she nevertheless believed her role as a journalist involved a sacred trust: to follow the facts as far as they would take her; to pursue the truth at all costs; to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. She did all three with regularity until the end.

Elaine, during our numerous editorial exchanges, offered me a first-rate education in how to edit and publish researched nonfiction, perhaps to the chagrin of those authors who’ve followed her. The key was to “never to be afraid to look stupid”; to clarify and keep pushing when you’re not clear on something; to keep asking questions until you’re satisfied. To fight over every word, every footnote, as the need arises. And we did, it seemed, fight over everything. Those initial Handover editorial rounds were bruising, unlike anything I’d experienced before as a publisher and editor. But as hard as it was, she never took it personally, as she trusted that we had her own, and her book’s, best interest in sight. She trusted in the process.

And in the process, she helped to reshape the direction of the press. Having been through the fire with Elaine, we knew better how to do these kinds of books, and knew, from her research, that one of the primary consequences of the sale of Canadian publishing to foreign interests was the decline in researched nonfiction. There was a gap in the market that needed to be filled, but more importantly a gap of intellectual responsibility. She fervently believed, despite her noted concerns about Canadian nationalism, that Canadians should be in charge of which Canadian stories were told. And that it would take Canadian writers and publishers to hold the powerful within Canadian society accountable. Elaine felt an intense sense of duty to tell the truth, and hated, as she called them, lying liars who lied. She used her formidable intelligence and research skills to untangle those lies, and we’re all better for it, and as another journalist wrote to me this week, now far lesser for her loss.

What drove her was her indomitable curiosity about just about everything. She loved to know things, and grew infuriated when the standard account didn’t make sense. This curiosity led her to begin digging into the origins of COVID when we were all in lockdown, reading the scientific papers, and discovering right away that there were things that didn’t add up; it led her to uncover connections between Winnipeg’s National Microbiology Laboratory and the labs at the centre of the COVID outbreak in Wuhan, and gather evidence of the Chinese government’s infiltration of this lab that would have national political ramifications thereafter. What amazes me about the research that became her On the Origin of the Deadliest Pandemic in 100 Years is that, though it was perhaps the first serious book-length enquiry into the origins of COVID in the English language (quite a feat, I must say, for a provincial publisher!), it has stood up remarkably well, with the consensus opinion moving closer and closer to Elaine’s own over the ensuing years. She followed the facts where they took her, and as usual, she ended up pretty close to the mark.

Her last book started with a January 1st, 2022 email from psychologist and Native Studies professor Roland Chrisjohn asking her to investigate “‘the cover-up’ of the Canadian government’s ‘genocide’ of Indigenous people.” But in her research, she became pre-occupied by questions of what was known when, by whom; and how she, growing up in the prairies, hadn’t known about the plight of Indigenous people in the surrounding communities. She turned her sharp journalistic eye on herself, and in the process wrote a kind of journalist’s autobiography and an investigation into the mechanics of what she calls obliviousness. The book is also an investigation of Indigenous health, segregated hospitals, and how the government used the lure of health care to conduct unethical experiments on wide swaths of the Indigenous population. There are some very disturbing revelations that Elaine uncovered by doing what she did best: following the trails of footnotes to uncover what had up to now largely escaped notice. Growing Up Oblivious will be published at some point in early 2026; it may well be her most important book.

When it became obvious that we didn’t have months but weeks, and then, really, days, I went up to Toronto to spend Monday and Tuesday with her in the Palliative Care Unit at Bridgepoint to work on the final edits and the conclusion. She was surrounded by family and friends who’d flown in from around the world to be with her. Though her body had completely failed by this time, and she was self-administering her pain medication as we spoke, she remained as sharp, funny, and caring as ever. We worked on a round of final edits and questions until she needed a rest; then did a second round; she did a long, wide-ranging audio interview with Marci McDonald about the book and what she uncovered, and was brilliant at it despite everything; then she shifted gears again, devoted to the attentions of her daughters and friends who were waiting for her. The next day she did another long interview with a national radio program and then we worked on the last paragraphs of her conclusion, arguing over word choices as if we had all the time in the world. She never, she told me, liked the word decency: it was a weasel word, could mean whatever you wanted it to mean. We needed something more specific to the issue at hand. We went back and forth for a while, and then it hit me. Dignity? “Yup. That’s it. Now let’s cut the rest of the fat and get it done.” And so we did.

There was so much love in that room, so much laughter, so much dignity, that it dispelled death’s shadow. It was a pleasure and honour to be there among her loved ones, if only for a little while. She seemed able to keep everything in those final days in perfect balance, the professional alongside the personal. Though perhaps, for her, that distinction wasn’t as sharp as it was for others. It didn’t seem possible that, when I took my leave, she’d be gone in less than 48 hours. And though I spent this morning watching her funeral, I still can’t quite believe she’s gone.

Elaine once described herself as aspiring “to be a happy warrior for the public good.” She was that. She was fierce, and tough as nails. But she was also a warm, beautiful person, matriarch to what I’ve learned is an incredible family, and a very good friend. She was, always, inspiring, and never more than in the last days; she approached her fate with resolve. I still haven’t entirely processed these last, intense few weeks, those days alongside her and her family and friends at Bridgeport, but I’m grateful once more for the gift of her time, intelligence, care, and compassion, and we will all at Biblioasis try to live up to the example she set.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

In good publicity news:

- Sacred Rage: Selected Stories by Steven Heighton was reviewed in the Globe and Mail: “[Heighton has] a cool mordant tone and sharp eye for human indignities at once sad and funny; an ear for how actual people sound and the confidence to let them sound that way on the page.”

- We’re Somewhere Else Now: Poems 2016–2024 by Robyn Sarah was featured on The Walrus’s list of The Best Books of Fall 2025.

- Marcello Di Cintio, author of Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers (Sep 30), wrote an op-ed for Maclean’s, “Canada Runs on Serf Labour.”

- Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet (Nov 11) was reviewed in Publisher’s Weekly: “The author once again proves his mastery of moody psychological thrillers.”

- Vijay Khurana’s The Passenger Seat was reviewed in Booklist: “A disquieting and beautifully written warning of young adult masculinity gone terribly wrong. Strongly recommend to readers interested in chilling, psychological crime fiction and the concepts in Netflix’s popular drama Adolescence.”