The Bibliophile: “Arnhem”

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

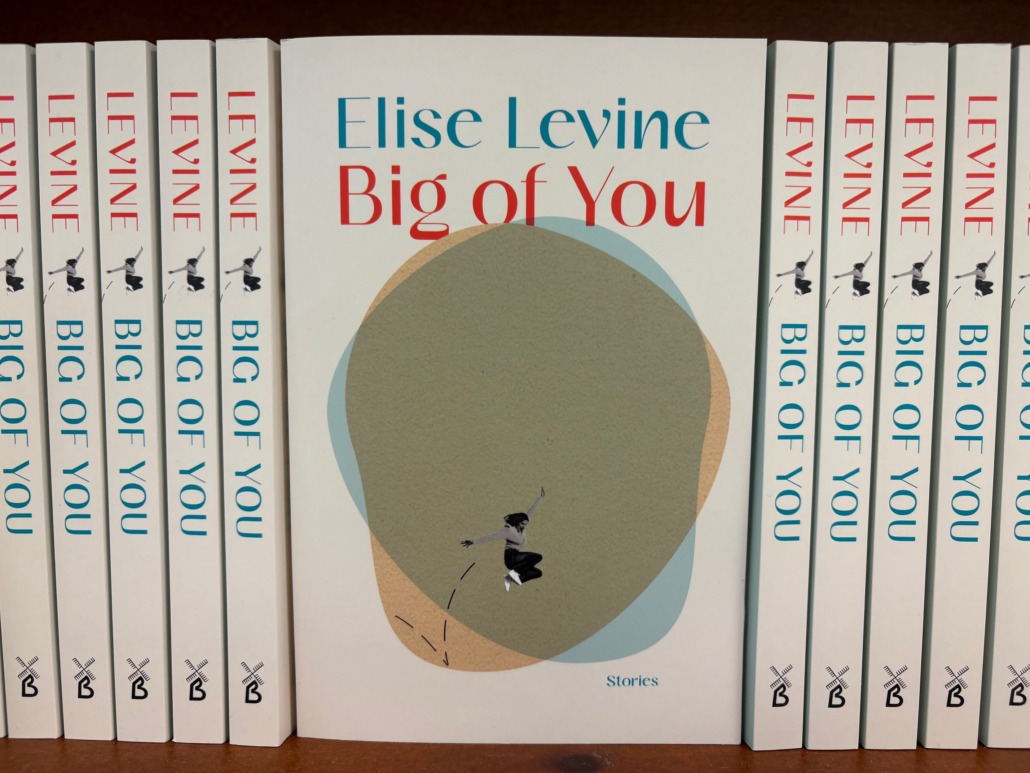

Elise Levine’s Big of You comes out next Tuesday, September 9 in Canada. I’ve been waiting, with anticipation, for about six months—ever since reading that first story on my work computer between emails—for everyone else in the country to pick up this unsettling, strange, beautiful book.

Big of You ranges across Europe, North America, and space. It includes all sorts of characters, from a mythological, millennia-old creature, to a nineteenth-century inventor and photographer, to a group of older women vacationing in the desert. What I find most stunning about Levine’s writing is her ability to convey the expressive interiority of each character. Tonally, her characters are wildly, humourously, iconically individual. These are some of the realest people I’ve ever encountered in fiction (and by real, I mean so exceptionally unique they border on the surreal).

Below is an excerpt from Big of You’s opening story, “Arnhem.” Coincidentally, this piece also appeared in Best Canadian Stories 2021 (edited by Diane Schoemperlen). I hope you’ll love this one—and the others—as much as I do.

Happy reading,

Dominique

Publicity & Marketing Coordinator

An excerpt from “Arnhem”

My husband leaves—I asked him to, or I didn’t, I can’t keep it straight—and I’m thinking, two girls on a hill. Heidelberg, or Conwy in North Wales where there’s also a castle. Two girls, telepathic as ants, making fast along a wet street. Oxford or Bruges. One girl’s freezing in her white summer dress. The other girl’s clad in army surplus pants and a baggy turtleneck sweater. Both of them seventeen, smug as cats, having blown off the archaeological dig on Guernsey, for which they’d secured positions six months earlier by mail. Mud labour, fuck that shit. On the appointed start date they simply hadn’t shown. Instead they thumb around, do all the things.

In a fancy café in Brussels, they order frites, which arrive on a silver platter, grease soaking into the paper doily. North of Lisbon they sleep on a beach one night. They run out of money in Paris and panhandle, not very well but they get by.

Who do they think they are?

Who did I?

I think we went to the zoo in Arnhem. I think we met a composer at some youth hostel who was from Arnhem. We met two young Italian men at a hostel in Mons. No one else was around and they tried to kiss us near the bathrooms when we went to brush our teeth that night. One of the young men forced one of us against the wall of the repurposed army barracks and thrust his pelvis a few strokes, while the other man stood back with the other one of us and watched. One night in the hostel in Amsterdam there was a phone call for one of us, and we both trundled barefoot down the stairs to the hostel office in our prim cotton nighties. Turns out one of our grandmothers was dying, the grandmother of the one of us who still had a grandmother.

I was the friend. We were friends.

I slept beside her in a roomful of older young women, all of us on cots half a foot off the damp floor. This was Cambridge. Dew on the windows all night, late June. The women were real diggers, by day excavating a nearby pre-Roman site. The men diggers, including my friend’s older brother who we were visiting, and the reason we’d dreamed up the scheme of ourselves volunteering on a site, slept in another large room, down the hall—so much for the men. But the women—solid, practical, tough. Intimidating to the extent that when I say I slept, the truth is I barely did, cold, legs aching, bladder wretched because I was too scared to get up. To be weak. To even think it. Be that person.

Which one was I?

Not the one in the summer dress. The one in the Shetland turtleneck.

*

If I were telling this to my husband, I’d say: the next morning in Mons the sky was clear. Awake for much of the night, my friend and I rose early and packed and picked through the continental breakfast array in the main hall. Individual portions of spreadable cheese wrapped in foil. Crisp rye flatbreads. Ginger jam. I’d never seen anything like it. The Belgian couple who managed the hostel, in their mid-thirties probably, kindly asked how we’d slept. We spilled the beans about the young men and the couple’s eyes grew round and their foreheads pinched. They would have a word with those guys.

By the time the couple did, if they did, and it’s true we believed them, my friend and I were gone.

*

We left Lisbon broke and caught rides up the coast. Mostly guys, some with their own ideas. Sometimes a woman who’d ask if we were okay. We were okay.

*

The beach was small with large-grained sand. We didn’t bother to take our shoes off.

The man who drove us there was slight of build. His mustache was light brown. At dusk he parked on the street and led us down to the water where we thanked him and said goodbye. He’d asked if we wanted to sleep on a beach that night and we’d said yes, please. Anything for an adventure to recall later in life. To say, How cool was that?

The sea frothed at our feet and the air smelled of brine. We toed a few half-circles and the sea erased them. We stretched our backs, yawned. He refused to take the hint. Thank you, okay?

He made himself understood then. He was spending the night with us. He’d called a buddy from the roadside café he’d taken us to earlier, where under his guidance we’d eaten squid in black ink very cheap and drunk cheap wine. Soon his friend would be here to meet us too.

It’s not like the driver had a tent or sleeping bags. Was there even a moon that night? There was a family camping nearby. A woman, a man, a child maybe eight-nine years old. They had a tent. Sleeping bags, no doubt. Judging by the track marks, they’d dragged a picnic table over, and the fire on their portable stovetop burned brighter while the sky grew darker and the man and my friend and I sat on the sand waiting, he for his friend, my friend and I for some notion of what to do, clueless as sheep.

It grew dark-dark. A flashlight made its way toward us. It was the woman. With her nearly no English and our no Portuguese and a little French between us, she ushered my friend and I into the tent with her husband and son.

How did we all fit? I must have slept the sleep of the dead, for all I can remember of the rest of that night.

*

When we first got together, my husband complained I slept like a swift. When things went from infrequently to occasionally bad to totally the worst between us, he said I slept like a fruit fly.

I pull the covers over my head. He’s not here to stop me, he’s at a friend’s—his, not mine. A week since yesterday. Good thing I brought my phone with me, light in darkness, all that. Especially with the news bulletins the past few days. Will I be okay? Will he? I hit his number and hang up when he answers. He immediately calls back, probably to yell, and I press piss off.

I ferret my arms out from beneath the covers. Stop calling me, I text-beg. Please.

For the next hour, while I still have my phone on, and for the first time in several years, he does as I say.

*

Around midnight I run a bath. I’m thinking again about the beach in Portugal, the family’s tent—the next morning my friend and I woke and stretched and crept back out. The driver lay curled like an inchworm on the sand near the waterline, no friend in sight.

He did drive us back to the highway, game of him. We girls, young women, once again stuck out our thumbs. Auto-stop, they call it there.

I switch off the bathroom light and climb in the tub for a long soak. My phone is still off, but I’ve got it holding down the toilet seat, in case.

My husband is in IT. He’s never once in his life hitchhiked. Like never even tried? No, he said on our first date, dinner at a pasta bar before a movie. Pale noodles, pale sauce, what can you expect for Cleveland, I thought, having recently moved there for the second of what turned into a seemingly endless stream of visiting assistant professor gigs. Before adjunct was what I could get. Now, not even that.

Like not even once? I’d pressured him that night over dinner. Never ever?

My date—who became my husband, at least for awhile, if I understand his intent by hightailing it to a friend’s, if I understand my own intentions—said no in a way that I knew to shut up about it for good.

*

Before he left us that morning by the side of the highway, the Portuguese driver tried to kiss me. I bit his lip to stop him. Where had I ripped that idea from? Some movie or book.

He got mad. Pushed me from him and fingered his mouth. Looked like he was considering options.

Later, in the back seat of our next ride that day—a Spanish couple returning from holiday, non–English speakers—my friend turned to me and said, I thought he was going to hit you. Why on earth would you do that?

I shrugged her off. But I’d also thought he was going to deck me. Some memorable story, one for the ages, something to one day tell the kids.

*

Weeks before Portugal, immediately after the phone call at night to the hostel in Amsterdam—when my friend learned her grandmother had cancer, and might not make it, and I took this news in grave solidarity, assumed a mournful expression that said I understood, I was by my friend’s side forever in all things—we sat on the floor outside our hostel room, nighties tucked around our legs. The old woman. The fights she fought with my friend the raging vegetarian, she of the curly hair she refused to tame. The stubborn fact of the fierce old creature—gone? Weird to think. But I nodded, weird I knew. The previous summer my father had an affair, and my mother told me about it, and now I told my friend about it. How the woman called my mother on the phone and said she and my father were in love. You’re only in love with his credit cards, my mother told the woman.

My friend put her feet flat on the hostel floor and rocked back against the hallway wall, she laughed her ass off. My god, she gasped. What a stupid cliché.

Earlier on the trip, fresh off the plane, well before we’d hit the road thumbs out, we’d stayed in London, and things hadn’t gone so well between us. At Trafalgar Square, on our third afternoon away from home, my friend undertook a spat with me. Talk to me, she semi-shouted. You literally dumb bitch. You need to tell me what you’re thinking, share your thoughts. Otherwise I might as well have left you at home.

The sun is nice today, the sun is too hot. Another beer, why not. Look at that old man over there. In Madrid, I told her I was afraid of morphing into one of the numerous homeless some day. You won’t, she said airily, you have family, friends. This sun is too hot.

*

I will share this: after my friend’s first suicide attempt, when we were fifteen and she was in the hospital over March break, I declined her single working mom’s invitation to host me at their house so I could help my friend through this difficult period. Instead I went to Myrtle Beach with my parents and little brother. Every afternoon the sib and I rode the Monster, tentacled and huge, at the sleazy mini-fairgrounds down the street from our efficiency motel room. Mornings we crossed the street to the hotel that actually was on the beach and baked in the sun by the heated pool. We swam too, hotfooting across the sugar sand to plunge in the icy waters, before reverse scampering and jumping in the pool to feel our skin burn. What else? I got mild sunstroke on our last day. For six bucks in a tourist shop, I bought my friend a pickled octopus jammed into a small jar.

You bet it was expired. Worse, by fifteen my friend had already gone vegetarian. When I got back home, more red and blistered than tanned, I paid her a visit in the hospital, and presented my gift. The look on her face. The shapeless blue gown, the big bandage around her wrist.

This was before Europe. I had no excuse. It was before my friend told me, that night on the Portuguese beach—sitting on the sand beside the driver who spoke little to no English, waiting for his friend to arrive, and before the family with the tent rescued us, that time in between, when the scope of our situation was beginning to sink in—that I really did not want to lose my virginity this way. Believe her, she knew all about it, having lost hers that spring, in the sleeping bag she’d borrowed from me, so she could go camping with this guy from our history class. He’d been a child actor in popular TV commercials and evolved into a cute teen actor doing same. Years later, years after this night in Portugal, he became a handsome adult actor, with a dimple so deep it nearly cleft his chin, and portrayed a cooped up astronaut in a popular show, and penned screenplays about the world wars, assigning himself the tortured-hero roles.

The night my friend and I slept in the tent in Portugal, I hadn’t heard the ocean waves, though they couldn’t have been more than twenty, thirty feet away. I hadn’t felt the pounding. Like I said: sleep of the dead. Those waves crashing closer, shuffling farther out, and neither my friend nor I possessing a clue about tides.

In good publicity news:

- Two Biblioasis titles are featured on the inaugural Fall 2025 CIBA Booksellers’ List: Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers by Marcello Di Cintio and Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way by Elaine Feeney.

- We’re Somewhere Else Now by Robyn Sarah was reviewed in the Seaboard Review: “Sarah’s verse is an antidote to the soul’s virus . . . Her diction seems so direct, but between the words and lines she meditates in musical nuance and wit to cast doubt on simple and complex truths.”

- On Oil by Don Gillmor was reviewed in The Book Beat: “A concise state-of-the-horror appraisal of humanity’s addiction to petroleum products, combining first-hand experience, historical research, and interviews with petroleum experts.”

- Ira Wells spoke about On Book Banning in an episode of Howl CIUT.FM.

- Russell Smith was interviewed about his novel Self Care on the Get Lit Podcast. Self Care also appears on Our Culture Magazine’s list of Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2025 (Part 1).

- The Passenger Seat by Vijay Khurana was reviewed in Anne Logan’s I’ve Read This.