The Bibliophile: Welcome to work but not to remain

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

An introduction to Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers by Marcello Di Cintio

In Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers, which publishes next Tuesday, Marcello Di Cintio travels across Canada (from the Okanagan, to Leamington, to Goose Bay, Newfoundland) to document the experiences of migrant workers, destabilizing the popular notion of Canada as a safe, welcoming space where migrants can escape the hardships of their home countries.

Contrarily, Di Cintio highlights a recent UN report that describes the Temporary Foreign Worker Program as a “breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery.”

There was so much I didn’t know about migrant policy and programs, about the prevalent unsafe housing, constant harassment, and unstable pay experienced by the workers every day. Or I knew about some of it, but only vaguely, at the back of my mind, the way I imagine millions of Canadians “know” about these issues. Precarious is filled with many of the harrowing, chaotic stories of precarity that make up the modern migrant experience in Canada. In a time of heightened, near-propagandistic Canadian patriotism, Precarious feels like such an important book to recalibrate our sense of identity, and our sense of what can be done to improve, rather than abolish, migrant labour in Canada.

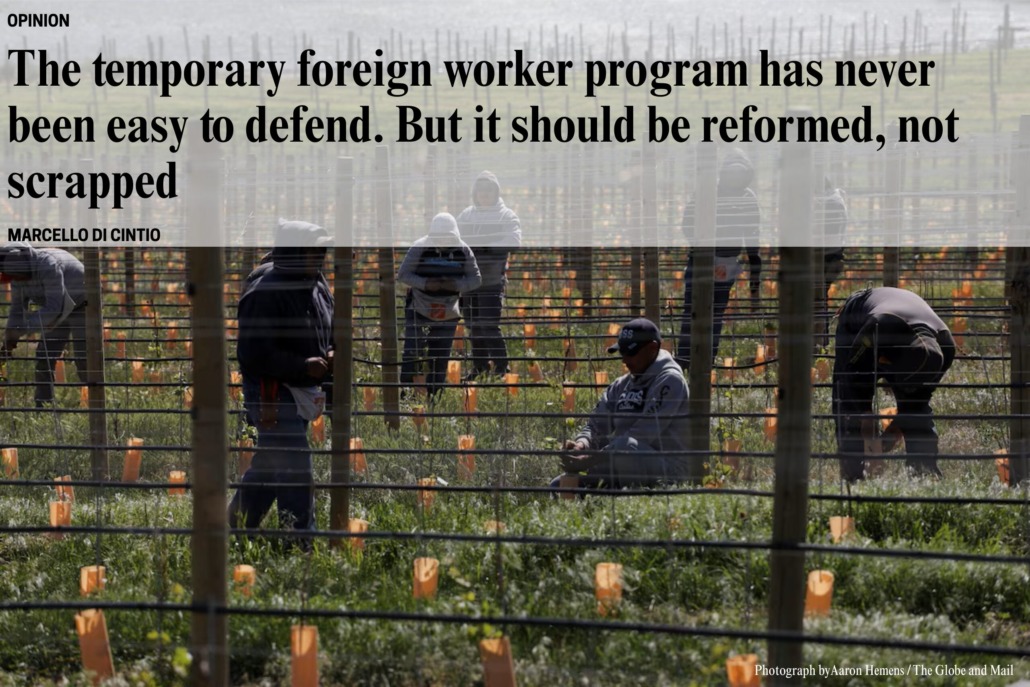

I recommend taking the time to read Di Cintio’s beautifully angry op-ed in today’s Globe and Mail, which he writes in response to Poilievre’s call to scrap the TFWP and deny visas to new migrants:

“I wonder . . . how many see the irony of being lectured about the ills of foreign labour by a recently unemployed man from 2,600 kilometres away—about as far from the riding as Chihuahua, Mexico—who showed up to take the job of a local resident.”

And I hope you’ll find the time to read the following excerpt from Precarious—taken from the introduction—which lays the groundwork for the book by pulling from Di Cintio’s familial experiences of migrant labour, and how these differ drastically from more recent experiences uncovered in later chapters.

Dominique

Publicity & Marketing Coordinator

An excerpt from Precarious

Introduction

My grandfather was a migrant worker before such a thing existed.

Amedeo Sorrentino was born in 1923 and hardly a man when Mussolini forced him into the Italian infantry. In my favourite photo of him, he is wearing his army uniform and holding a cigarette between his fingers. My grandfather never smoked, but the photographer told him the cigarette would make him look older. After the photo was taken, the army shipped Amedeo across the sea to North Africa, handed him a rifle, and sent him out into the desert. British soldiers quickly decimated his regiment, and Amedeo was taken prisoner. He spent the rest of the war in a London POW camp.

After the war, Amedeo returned to his hometown of Lanciano and learned that his mother had died. Shrapnel from a grenade struck her in the back and killed her instantly as she sat in the village square with Amedeo’s youngest brother on her lap. My grandfather never hesitated to retell his war stories, and they were harrowing, but he didn’t like talking about what his family endured during those years. “The real war was back home,” he’d say before growing quiet.

My grandfather met my grandmother, Giulia, a few years later. Amedeo was not the first suitor to come calling. There were “lots of boys to choose from,” she once told me. One was a police officer, but policemen were not allowed to marry until they were thirty, and Giulia didn’t want to marry an “old man.” She chose Amedeo because he was the only one to make her laugh. Their courtship involved walking back from church together with family chaperones following a few paces behind them.

Because they were both poor, Giulia and Amedeo waited until after Easter to announce their engagement so they wouldn’t have to give holiday gifts to each other’s families. Giulia’s mother, Guiseppina, did not approve of the engagement. “Why do you want to marry someone poorer than you are?” she asked her eldest daughter. They married on a rainy day in 1948 after their borrowed car got stuck in the mud and had to be pulled free by an ox. The family ate the wedding dinner in Giulia’s parents’ bedroom, the largest room in the house. Afterwards one of Amedeo’s friends set off firecrackers he made from unexploded artillery shells he’d found in the fields.

Amedeo vowed never to leave home again. He’d found happiness with Giulia and wanted to raise a family with her in the country that he loved. Their first daughter, my mother, was born later that year, then two more girls in the years that followed. Amedeo toiled as a tenant tobacco farmer to support them. The landowner allowed Amedeo to keep and sell only half of the harvest. With no sons, Amedeo did most of the labour himself. He found extra work at his uncle Nicola’s olive oil press. Though Amedeo had little education—he’d reached only the fifth grade before leaving school—he was good with numbers and did his uncle’s accounting.

For all his love of Italy and his promise to never leave it, Amedeo knew he could never properly provide for his family by working on someone else’s farm. Men were leaving Italy every day to find work abroad, and Giulia persuaded Amedeo to follow his sister and brother-in-law to Canada, at least for a couple of years. Amedeo obliged and set off in 1956. He sent back a photo of himself waving from the deck of the Canada-bound ship. A note on the back written in black ink read: “As soon as I lifted my hand, my first thought was of returning soon to my family, and to my beautiful Italy.”

Before World War II and the Great Depression preceding it, most immigrant workers to Canada came to develop the agricultural economy of the Prairies. After the war, though, Canada’s booming industrial economy needed urban workers: people to build things, not just grow things. Many Italians ended up on construction sites in cities like Toronto, Montreal, and in my grandfather’s case, Calgary. Amedeo poured concrete during the day and tended to greenhouses at night. Years later, my grandfather would look out at the Calgary skyline and point to the buildings he helped build, including Foothills Hospital where I was born.

With the money Amedeo sent back to Italy, Giulia was able to buy a bicycle for her daughters and a record player for herself. One day, a vinyl record appeared in the mail from Canada: a recording of his cousins singing songs in a small Calgary studio. Amedeo was on the album, too. He had recorded a message for his wife and daughters, telling them that he loved and missed them. There were no telephones in Lanciano at that time, and this was the first Giulia had heard her husband’s voice in over a year. The arrival of the record was both a blessing and a tragedy. For all the marvellous joy it brought to hear Amedeo’s voice, the record reminded everyone that he was far away.

My grandfather didn’t want to stay in Canada. He wanted to save enough money to build a better life for his wife and daughters back home. Maybe buy some land and a bigger house. He wanted to be temporary. After two years, though, he and Giulia decided that it would be better for the family to live in Canada than to reunite back in Italy. Nonno resisted, but Nonna was stubborn. With the money Amedeo had sent them, Giulia and their daughters boarded the RMS Saxonia for the long, seasick journey west. The girls insisted on bringing their new bicycle with them. It lasted for decades, and I used to ride it around my grandparents’ neighbourhood when I was a child. Nonna left the behind the album that brought so much happiness for the family with Amedeo’s sister, Ersiglia. When Amedeo and Giulia returned to visit Italy years later and inquired about the album, Ersiglia claimed the mice ate it.

I doubt Amedeo and Giulia knew the role their whiteness played in their journey to Canada. The entry of non-white immigrants was restricted until 1962 when the federal government expunged overt racial discrimination from our immigration policy. Even afterwards, though, bigotry proved a tough habit to break. Anyone from anywhere was now permitted into the country as long as they demonstrated they could succeed here, but preference was given to people from Europe. And only Canadians from the United States and certain European and Middle Eastern nations could sponsor the immigration of their siblings. In the early sixties, my grandfather sponsored his sister and two brothers to come to Canada, a privilege he wouldn’t have enjoyed had he been Black or Asian.

My nonno died in July 2020 during the first fraught COVID summer. He’d been living in an extended-care facility since a stroke felled him a couple of years earlier. Nonno received initial treatment at the Foothills Hospital, and during a particularly painful injection quipped to my mother, “I never should’ve helped build this place.”

Due to the pandemic restrictions, fewer than fifty invited family members, masked and distanced, attended his funeral mass. When I stood at the front of the church to give his eulogy and looked out at the sparse attendees, I knew that the church would have overflowed with mourners had Nonno passed even a few months earlier. My grandfather was one of the first links in an immigration chain that brought dozens of families to Calgary. No doubt hundreds of the city’s Italians can trace their history back to my grandfather’s reluctant passage across the Atlantic.

Circumstances have changed for workers from abroad since then. Even though my grandfather came to work and never intended to stay, Canada granted him landed immigrant status upon his arrival. He had a choice to immigrate or not. Had my grandfather made the same journey even a decade later, he’d likely be considered a “temporary foreign worker”: welcome to work but not to remain. A labourer, yes. Not a link.

Nonno’s passing made me think of his contemporary counterparts. My grandfather only wanted the best for his daughters, and he was willing to sacrifice years away from them for the opportunities Canada would eventually provide. No doubt today’s migrant workers make the same bargain. But what does it mean to voyage far from family to a nation that wants you to work but doesn’t want you to stay? Bring your arms and backs, Canada pleads, but leave the rest on the other side of the border. We need your sweat. We don’t need your stories.

But I did. After my grandfather died, I set out to hear the stories of migrant workers in Canada. I knew nothing about these newcomers. I wondered about their days in our country, the lives and loved ones they left behind, and what compelled them to first make their long journeys here. I wondered, too, if they believed their time in Canada made up for their sacrifices and absences. Was our country worth it?

I spent the following three years travelling the country to meet workers and their advocates, pausing my wanderings for intermittent pandemic shutdowns and travel restrictions. I quickly learned that my image of a migrant worker was sorely limited. I thought I’d be spending all my time speaking to Latino farmhands and Filipina “nannies.” But I found that migrant labour exists within all aspects of Canadian society. Temporary workers are everywhere. They build our homes, drive our trucks, clean our offices, and pour our coffee. Many of Canada’s post-secondary institutions are propped up with the foreign tuition paid by international students who, most of the time, are also migrant workers. The complexity overwhelmed me at times. The more people I spoke to, the more threads emerged. I wish I could have followed them all, but the diverse workers I did manage to speak to expanded my perspective of what migrant labour encompassed.

For the most part, I heard the kinds of stories I expected to hear. I learned about how calamities back home—a sick child, a dying wife, a hurricane—compelled people from around the world to seek financial opportunities here. I heard stories of redemption, reinvention, and romance. I learned about workers sending their overseas families gifts of maple syrup and Toronto Maple Leafs caps to stand in for the physical embraces their long separation denies them. I smiled at the baby photos on their cellphones. I cheered workers on soccer fields and watched the dance videos they recorded in their greenhouses. I heard about lovers the workers had left back home, and the lovers they found here.

What I didn’t expect, though, was how often Canada itself was the source of the migrants’ trauma. Despite the sufferings many workers escaped, a sea of troubles awaited them here. Nearly every worker I spoke to had been done wrong. Cheated. Threatened. Beaten. The abuse nearly always came at the hands of my fellow citizens. I realized I wasn’t just looking into the lives of workers who’d long been invisible to me; I was seeing a Canada I didn’t recognize. The more I learned the migrants’ stories, the more I learned our own. And the portrait of Canada I started to see wasn’t flattering.

In awards news:

- Graeme Macrae Burnet won Australia’s Ned Kelly Award for Best International Crime Fiction, for A Case of Matricide.

- Mark Bourrie’s Crosses in the Sky: Jean de Brébeuf and the Destruction of Huronia made yesterday’s shortlist for the 2025 J.W. Dafoe Book Prize.

In good publicity news:

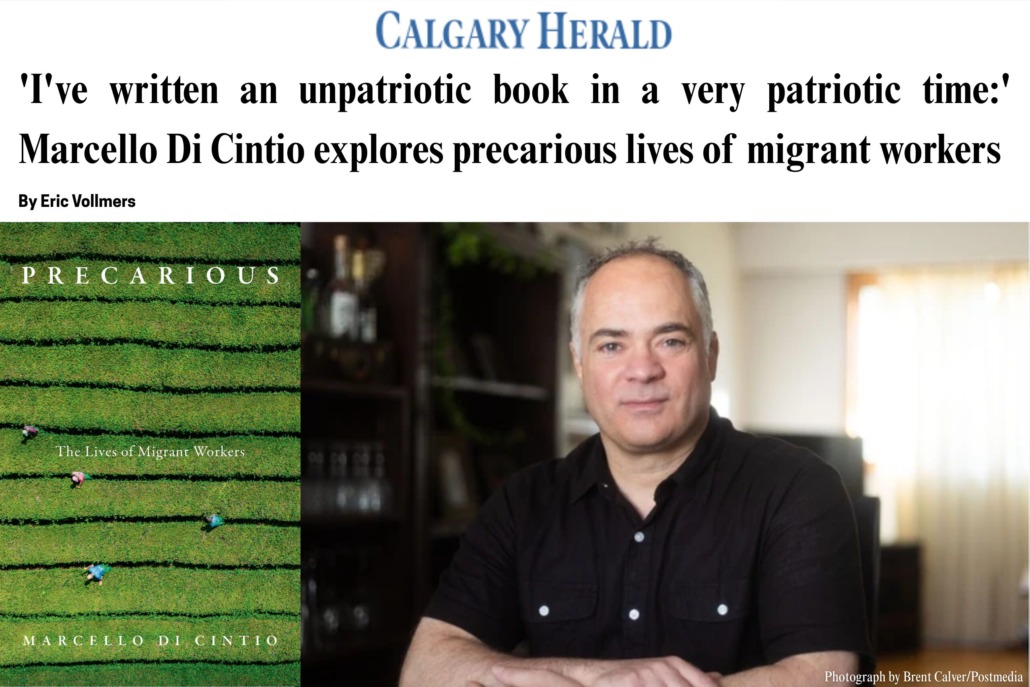

- Marcello Di Cintio, author of Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers was featured in several outlets this week:

- Interview in the Calgary Herald: “What started off being a book about other people, about these workers, really also became at the same time a book about us, a book about how Canada has treated these people . . . I feel I’ve written an unpatriotic book in a very patriotic time.”

- Op-ed in the Globe and Mail: “For a half century, TFWs have recounted stories of filthy and crowded bunkhouses, unsafe working conditions, wage theft, humiliation, physical and sexual assault, and all manner of cruelty. I heard many of these stories first-hand. Penalties for these crimes are too soft and too rare. Victims have little recourse.”

- Old Romantics by Maggie Armstrong was reviewed in Heavy Feather Review: “Brilliantly oscillates between a focus on the inner world of a flawed woman’s personal journey through the land of modern romance and a spitting commentary on what it even means to be a wife, mother, and woman in the 21st century.”

- Best Canadian Poetry 2026 edited by Mary Dalton was reviewed in the Washington Review of Books: “Reading Dalton, one really gets the sense that there was a poetic process enacting the selection process . . . I thank [Molly] Peacock for bringing the series to life, and [Anita] Lahey and Biblioasis for keeping it alive.”

- Self Care by Russell Smith was reviewed in That Shakespearean Review: “You can always count on Russell Smith for a straightforward technique that hits you in the solar plexus.”

- We’re Somewhere Else Now by Robyn Sarah was reviewed in The Tribune: “This collection grapples with contemporary life in a way that is both stylized and vulnerable . . . Sarah’s ability to tie scenes of everyday life to highly abstract concepts and ideas results in compelling poems.”