The Bibliophile: The Biblioasis Holiday Book Guide (Part II)

Recommendations from the Biblioasis crew!

We’re back with the second part of our Biblioasis staff picks, and I’m certain it will come as no surprise to anyone that we’ve decided to make this a three-part series.

There are just too many good books to share!

Please enjoy a few more of our favourites from 2025 that we think you should check out—and maybe you’ll find that perfect book gift in time for the holidays. Next week, look forward to our final recommendations, and a word from our publisher Dan Wells.

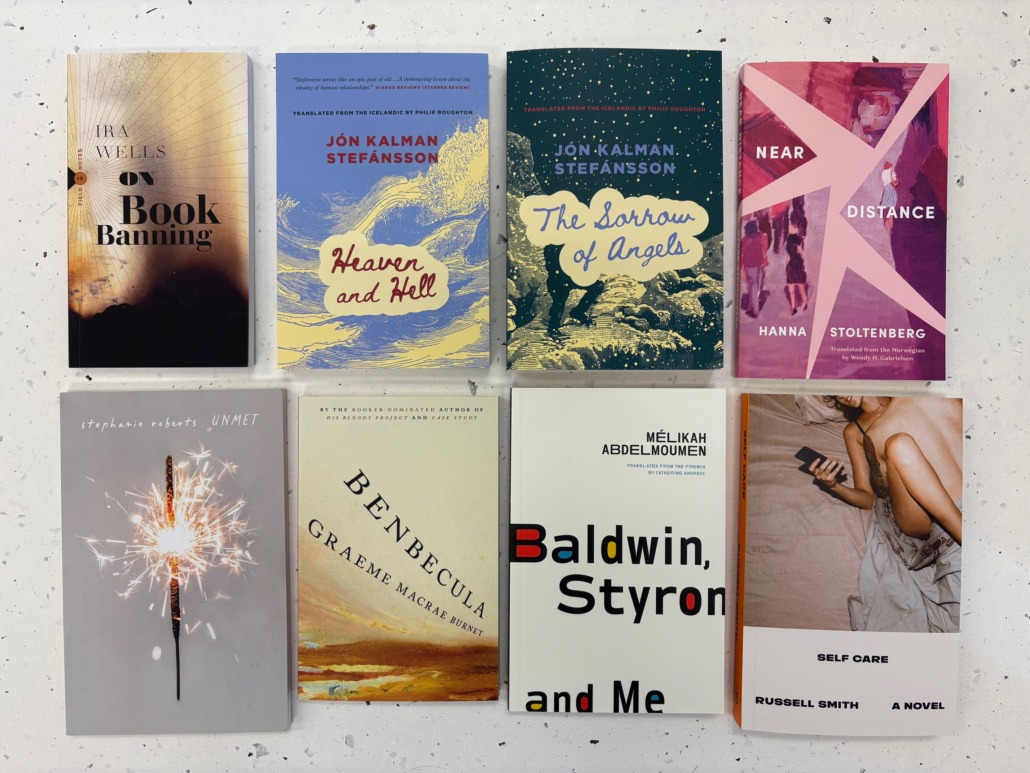

Ashley

Editorial Assistant

Hilary Ilkay

Sales Coordinator

By far the spiciest book I read this year, Russell Smith’s first novel in a decade is a propulsive, disquieting portrait of a young generation unable to make genuine connections and live authentically. Set in Toronto, Self Care stages an unlikely encounter between a burnt out, ennui-suffering freelancer named Gloria and a self-deprecating incel named Daryn. Through their increasingly troubling relationship, Smith explores power and sex and the harm posed by online communities and discourses. You will not be ready for the ending, which will get under your skin for days afterward.

Dominique Béchard

Publicity & Marketing Coordinator

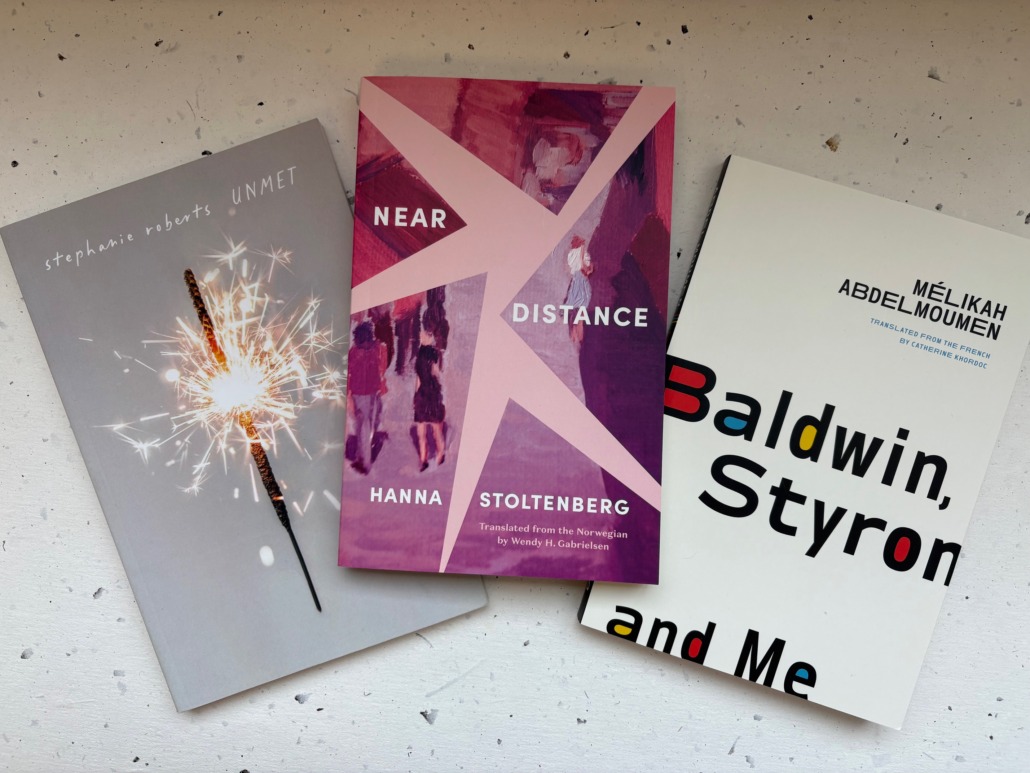

UNMET is an incredible poetry collection that doesn’t compare to anything else I’ve read. roberts employs an impressive range of registers—slipping from earnestness, to irony, to playfulness, to anger . . . But always, it strikes me, in service of the unexpected. The surprising leaps of diction and syntax make me feel like I’m leaning precariously over the known world into the open-hearted absurd. And I feel like an improved, more malleable human coming out of these poems.

Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen, translated by Catherine Khordoc

In 1961, James Baldwin spent several months as a guest in William Styron’s home. During this time, Baldwin encouraged Styron to write The Confessions of Nat Turner from the perspective of the slave; it would go on to win a Pulitzer, but also elicit controversy from the African-American community. Abdelmoumen doesn’t take sides, but rather creates space for dialogue about race and cultural appropriation that avoids binary thinking. This book champions a definition of identity that is “in a constant state of flux,” that depends first and foremost on listening to others—what she calls “the beauty of cross-pollination.” I’m not someone who is prone to optimism, but the hope at the heart of Abdelmoumen’s book softened last winter’s sharp edges. It would make a great new year read for anyone who wants to shake the bleak, the rigid, the alone.

Near Distance by Hanna Stoltenberg, translated by Wendy H. Gabrielsen

I read an ARC of Near Distance almost two years ago, before knowing I’d soon be working at the press. Though under a hundred pages, the tense, encroaching malaise of Stoltenberg’s debut novel has stayed with me. Near Distance portrays the tenuous relationship between a mother, Karin, and her adult daughter, Helene. Stoltenberg told me that Karin was based on the fathers she knew growing up: casually uninvolved, inclined to focus on themselves, emotionally distant. For such a short book, the character of Karin is so complex and strikingly herself; I still think of her frequently.

Ahmed Abdalla

Publicist

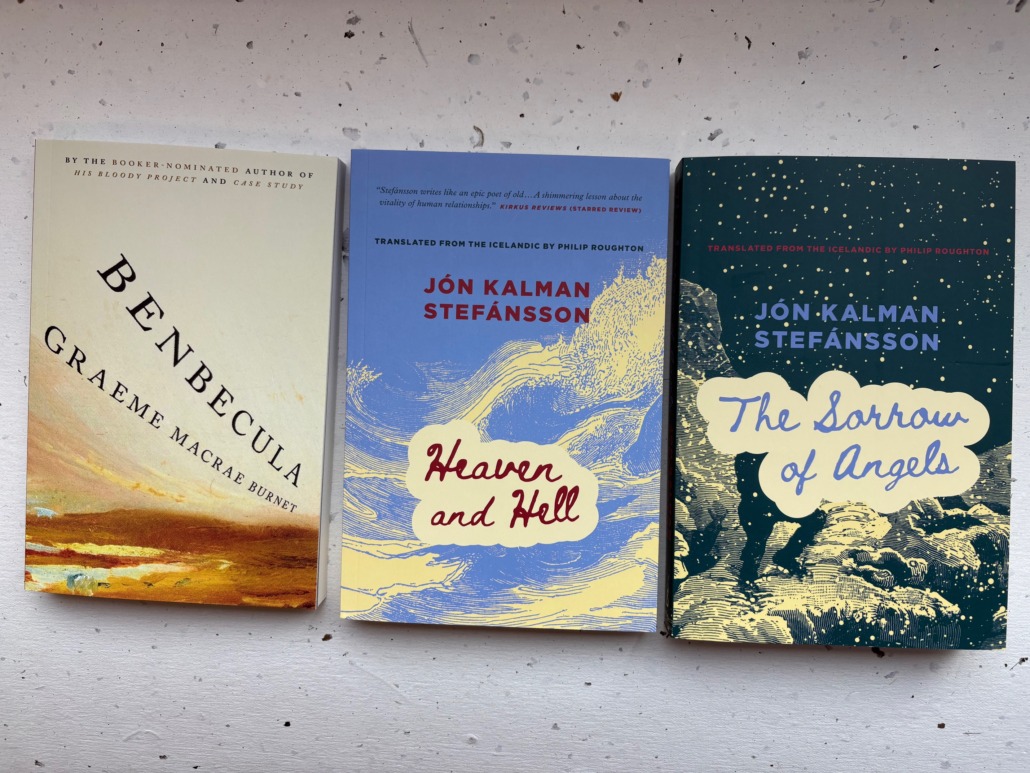

Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet

I’ve talked quite a bit about my love for Benbecula in a Substack post from last month, but the first time I read Benbecula, I read it in one sitting, and then I read it again. It’s a first person account of a murder and its aftermath in a small community. An incredibly engrossing read that I found difficult to put down. Sometimes if I walk past the copy in my apartment, I’ll pick it up and reread certain sections. I don’t know what it says about me that enjoyed this story of madness so much, but here we are. This story of real life triple murder on a remote Scottish island in the 19th century becomes a Jekyll and Hyde–like tale about madness and the slippery nature of identity. It’s a novel approach to true crime, darkly funny at times, about a man, living alone, haunted by memories and voices, slowly sinking into madness. The nonfiction afterword where Burnet describes the real life case and his research was also a delight to read.

Heaven and Hell & The Sorrow of Angels by Jón Kalman Stefánsson, translated by Philip Roughton

The first two books in Jón Kalman Stefánsson’s Trilogy About the Boy (look out for the third one, The Heart of Man, that’s set to be released June 2026) harkens back to the old Icelandic sagas. It’s the story of an unnamed boy in a remote Icelandic fishing village who loves nothing more than poetry and reading. In the first book, Heaven and Hell, his only friend dies, and he begins a journey that takes him out of the lonely fishing village and into a new community where he finds friendship and hope. The Sorrow of Angels has him embark on a new quest, with an alcoholic, melancholic mailman, across a brutal winter in order to deliver some important mail. It’s the stuff of epic: of men in search of themselves, battling against nature and despair. The whole trilogy is really a testament to the power of literature and the communities found around it. Stefánsson’s voice is absorbing and immersive throughout, and Philip Roughton has done an amazing job translating it into English. I think he’s so unlike any writer I’ve read recently, and to me that is among the highest of compliments. He’s an original, crafting these intense and lovely lyrical, small-scale epics, with wonderfully written character studies. Read him for all the beautiful ways he describes walking through snow.

Ashley Van Elswyk

Editorial Assistant

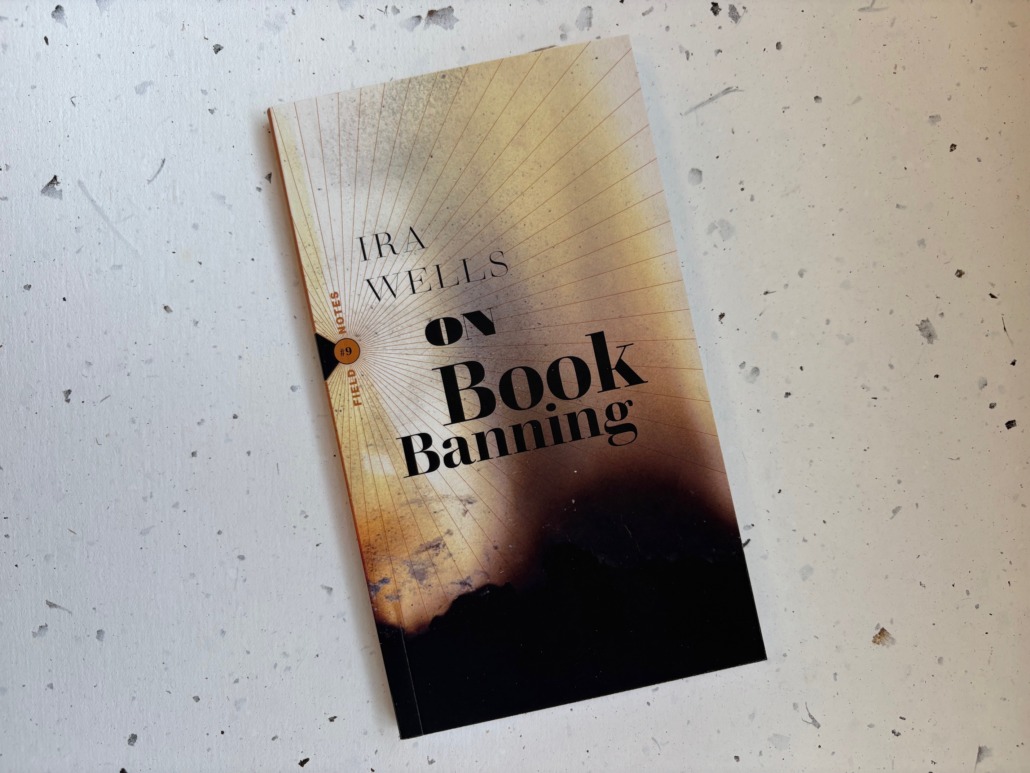

In this slim Field Note, Ira Wells offers surprisingly rich historical and contemporary context alongside personal experience to a topic that can sometimes seem like a vast, irremovable threat. Before reading Wells’s book, when I thought of book bannings I thought of the United States, or Alberta. The censoring of queer and diverse titles and authors, of older books, or of uncomfortable topics, wasn’t something that happened in places as close to home as the libraries and schools of Southwestern Ontario. But On Book Banning made me think more about what’s happening to our crucial centres of learning, and helped expand my knowledge of what book banning is, what constitutes it, and where we can take action to better prevent it. Here, Wells offers a passionate defense of our right to read, and we should all take that defense to heart before we lose these beautiful sources of knowledge and wonder.

In good publicity news:

- Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc) was featured on CBC Books’ list of Best Canadian Nonfiction of 2025! CBC also ran an article on Baldwin, Styron, and Me’s Carnegie Medal shortlisting.

- Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories 2025 were reviewed in Cemetery Dance: “Beautiful and uniquely collectible . . . Another fine set of Christmas ghost stories, perfect for the gray, dreary days that lead us into the magic of the holidays. As always, they are highly recommended.” The three Ghost Stories were also recommended on the So Many Damn Books podcast, and in the Washington Post’s Book Club newsletter.

- The Notebook by Roland Allen was reviewed on Jeremy Bassetti’s blog: “Gripping [and] insightful.”

- On Book Banning by Ira Wells was reviewed in Alberta Views: “This slender volume makes for excellent conversational kindling. More than a definitive treatise or clear prescription for protecting the right to read, it serves as a starting point for serious thinking about the question.”

- We’re Somewhere Else Now by Robyn Sarah was listed as one of California Review of Books’ Best Poetry Books of 2025.