The Bibliophile: A Conversation with Ira Wells

From the Biblioasis launch of On Book Banning

In March, Ira Wells joined us for the Windsor launch of On Book Banning. We recorded Ira’s discussion with our publisher, Dan Wells (no relation), and we’re delighted to bring it to you here as we look forward to its publication in the US this Tuesday, June 3.

Ashley Van Elswyk

Editorial Assistant

DAN WELLS: Your book, Ira, opens with a very personal story: that of a parent, you, sitting in a child’s library chair, your knees up around your ears in their school library, one of the occasions that certainly instigated the writing of the book. Would you mind starting the evening by telling us a little bit about this experience, and what the result was?

IRA WELLS: It did, yeah, not all great stories begin with an email from a school principal, but this one does. I received an email in 2022 from the principal of my kids’ elementary school indicating that they were initiating something called a “library audit.” And there was something about that phrase that struck me as interesting. By this point, we’d already been hearing a lot about the book banning that had been taking place in Florida and other places in the southern United States, and I wondered if “library audit” wasn’t just an innocuous, boring-sounding description, and if it came to Toronto, if that is what they would call it—a “library audit.” It turned out to be a little more complicated than that.

So, I joined a parent committee to see what was going on and we were given something called a TDSB—Toronto District School Board—Equity Toolkit, which we were going to use to evaluate books. Then we were asked to pick five books off the shelves more or less at random. And a couple of things jumped out at me immediately in this exercise. One is that if you were to actually use this toolkit, to go through and apply it to every book in the library, there is not enough time in your life to do it. And so at a certain point the principal became somewhat exasperated and said, “I just wish we could get rid of all the old books.” And I thought she was maybe kidding. At least, I hope that she was.

But the following fall, in the Peel Region (which is in the Mississauga area), in some school libraries, up to 50 percent of the books had been removed from the shelves. They really had gone through and got rid of all the old books, which was somewhat horrifying. But that’s the genesis of On Book Banning. I was working on something else, but the moment where I realized I needed to pay more attention to this was when all those books were liquidated from the shelves of Peel Region, because I realized I didn’t really have the vocabulary or the arguments to respond. I’m an English professor, but I didn’t have at the tip of my tongue the words to articulate why books matter, why banning them is wrong, and why we need to pay attention when this is happening in our society. Because it’s not just an American problem: it’s also happening here. That’s why I wanted to dive deeper into it.

DW: So, when you were sitting there in the library before the Peel cull, one of the things they did, if I remember correctly, is basically decide that any book that had been published more than fifteen years prior was too old to be on the shelves. They considered it “dangerous,” right?

IW: The situation in Peel was this: there was a student named Reina Takata, who was a Grade 10 student at Erindale Secondary School in Mississauga. She was the kind of girl who went to the library, ate her lunches in the library, was very familiar with the library. She came back after summer vacation in Grade 10 and realized that, in her estimation, half of the books were gone.

The CBC picked this story up and reported on it. We don’t actually know—there are 259 schools in Peel Region—we don’t know and will never know how many books were removed during this process. But we do know two things. One, as Dan said, they had settled upon this fifteen-year lifespan, so anything that had been published more than fifteen years beforehand was ripe for removal. And the second thing we know is, because these books were deemed “harmful,” they could not be donated to families in need, they could not be given to jurisdictions that could have used them. They were boxed up more or less like toxic waste and disposed of.

DW: We’ll get back to this idea of harm later on because I think it’s kind of central to how both the right and the left have talked about what they’re doing. Both the examples that we’ve started with are, I guess one could argue, examples of the left banning books or removing books from libraries. You also talk about things that have happened in Florida and elsewhere in the us. Do you want to give a bit of background about that side as well?

IW: Absolutely, and I think in some ways this may be the more familiar version of the book banning story. At least it was to me until I started paying more attention. There are a number of parents’ rights organizations, like Moms for Liberty, No Left Turn in Education, and there are Canadian counterparts. They’re sometimes described as anti-government organizations. And they got very interested in the content of school libraries during covid. They’re particularly concerned with books they call LGBTQ indoctrination. This could be anything that has a queer character, even, so something like Drama by Raina Telgemeier—a graphic novel that is very popular with the kids—or, not to mention, anything that has a sort of sex-ed dimension to it. But anything with a queer character. They’re also very interested in race, so anything that sort of smacks of what they would call critical race theory, or anything that casts slavery in a negative light. Including Toni Morrison. They go after these books, and they do it in a very specific way. They have game plans: they meet up in the parking lot beforehand, they have matching T-shirts, they divvy up their questions, and it’s almost like tailgating, and there’s this culture around it. They converge on school council meetings and they use their allotted five minutes, and they drag these meetings out—sometimes they’re seven hours long—and they’ve been pretty successful at getting books off the shelves.

So, this is the right-wing version, the evangelical version, the populist version. They do delightful things, like they’ve started to harass teachers directly by providing a list of books to a teacher and saying, “If you teach any one of these books, we’re going to sue you or bring some sort of legal action against you.” I’ve heard of lawsuits, the threat of lawsuits, against people who have the Little Free Libraries you may have seen around. If you have something they deem obscenity in those Little Free Libraries, they’ll threaten a lawsuit. And they will often threaten librarians with legal action or just make their lives a living hell. The free speech organization pen America has been very attentive to this and has been tracking the number of challenges. In 2023 or 2024, they put the number at ten thousand challenged titles. But there is also some research that shows between 83 and 97 percent of book challenges are never reported. So it’s almost certainly much, much higher than what we know.

What I found very interesting about the Canadian progressive version and the evangelical version is that they both seem to construe books as a source of contagion, as a source of harm, and they both advocate the same solution, which is to censor them, to get them off the shelves. I was very struck by the fact that you’ve got these two groups: progressive educators in Ontario and Southern evangelicals who appear to be political opposites in every possible way. Yet they think about books in a very similar way, and they have the same problem, which is they think books are causing harm to children, and they have the same solution, which is to ban them.

DW: I’m sure the principal in your children’s school would be horrified if you pointed out to her she was using arguments that a DeSantis conservative would use in Florida, and yet they were basically identical. Just for different purposes. But there’s something else that I think unites both the DeSantis conservative evangelical movement and maybe the more liberal one: they both deny that what they are doing is book banning—we should probably define book banning. And how does it relate to what you call in this book the “new censorship consensus”?

IW: That’s a good point, Dan. No one considers themself a censor, no one identifies as a book banner, which is why I think it’s really important to go back to the definition. The American Library Association defines book banning as the removal of a title from the shelves because someone deems it harmful. And what strikes me about that definition is how precisely it is describing the rationale of well-intentioned people on the political right and on the political left who believe that they are removing sources of harm from libraries.

I should say that the action the Peel Region took they described in their own words as an “equity-based book weeding process.” And that’s another term that we should unpack. Because weeding is actually something that librarians do. Weeding is a legitimate part of developing a library collection, and it refers to things like, if a book is falling apart, you weed it, if a book is out of date you weed it. It is a legitimate process, but again, to go back to the definition: the American Library Association says that while weeding is an essential part of the development collection process, it is never a deselection tool for controversial material. They want to have a very sharp line between censorship, which is not legitimate, and weeding, which is. And so, when the Peel Region says “oh we’re just doing this weeding process and getting rid of all the books we don’t find equitable,” that’s in fact an abuse of the weeding process and they are book banning.

DW: I want to also step back a bit and talk a little bit about this idea of harm. I have a sensitivity and appreciation for some of the arguments that are made about the idea of harm. You know, the idea that some books, some words, some language, can be triggering. What’s your response to that? What’s your response to the idea that what they’re really trying to do is not just ensure that everybody is represented in the library, but they’re trying to protect people from harm?

IW: It’s a good question, and it’s an unavoidable one. I would just preface my answer by stating that I don’t want to be misconstrued as saying that we should only have old books in the libraries or that we should only have what we would think back on as the kinds of books that we remember from our childhoods. I’m not advocating that at all. I think we should have diverse libraries, I think that the children who go to our schools need to be able to go to the libraries and find books that tell stories that they relate to, which includes having very diverse collections. I fully believe that children should see their own stories reflected in those pages. It’s not at all hard to find stories of LGBTQ-identifying people who say that they read a story or they engaged with a narrative about a queer character and that it changed their life, it validated their life, and that it saved their life. It’s not at all hard to find stories of people saying, “That book saved my life.” I think we should listen to them, and we need to be damn sure that those books aren’t banned and taken off the shelves.

Now, to the point about harm and what we do in the inverse case where someone says this book is causing harm—there are policies and procedures in place which are being abused in places like Pensacola, Florida, which is a place I look at in the book, where parents will use the book-challenging process to say “This book is not an appropriate book because it’s actually child pornography.” Or it’s LGBTQ indoctrination. The mechanisms that we have in place to take harmful books off the shelves are often weaponized against the material that we should be saving. So, that’s the first thing I would say.

The second thing I would say, and I’m just leaning into the policies of the school boards and of the libraries themselves, is that harm is not something that can be experienced subjectively by the person who is making the complaint. What I mean by that is, if I’m a parent and I’m outraged about something that I’m seeing in a book and it offends me, my offense, my personal offense, is not a legitimation, is not a rationale, for removing a book from the library or from the school. Because we cannot give every single parent veto power to remove books from the libraries or every single citizen veto power to remove books from the libraries. We live in a very large, very diverse, pluralistic society, and if we give that kind of veto power to one group, we have to give it to all groups, and this is not a paradox that we can work our way out of. We either defend freedom of information, which may include material that is found offensive, or we don’t, but I don’t think we want to live in a world in which everyone gets a veto power over what you get to read.

DW: You tell some great stories about writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates, who read Macbeth and found it gave him insight into Baltimore, life on the streets in Baltimore. One of the unintended consequences even of the Peel cull and picking the fifteen-year window is that there were many books that all of us would acknowledge need to be on every library’s shelves, like The Diary of Anne Frank or Obasan, or works of Canadian history that were cut. That were removed merely by being published before that date. And it seems to me that this approach is based on a lack of awareness of how publishing works. There seems to be this idea that we can remove old books because the new ones will fill all the gaps, but quite often, especially in Canada, because of the constraints on publishing, that isn’t possible either. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that.

IW: Yeah, absolutely. As you mentioned, the category of “classic” was one that the progressive educators in Peel were particularly hostile to. I know this because they had a little manual that they distributed internally that was then leaked, which is in the footnotes of the book. They instruct people who are doing this equity-based weeding process to cast particular skepticism towards what they call classics. Which they say are inherently Eurocentric and heteronormative and bad in other ways. I would just say a couple of things about that. One is that they are using the word classic as it was used about a hundred years ago, and I’m not kidding about that. Like when people talked about “great books” programs in 1925, that I think is what they have in mind. But certainly since the 1960s, the Western canon has been diversified and challenged, and certainly as far as University of Toronto students are concerned in 2025, the category of classic includes Toni Morrison, includes James Baldwin, includes Ralph Ellison, includes so many of the people who would be banned for being outdated in this new rubric.

By coming up with this arbitrary date, by saying “Okay, our libraries, our school libraries, will include everything published in the last fifteen years,” I think the rationale is that they are thinking the books need to reflect the life experiences of the students. And so if the students are fifteen, the books should be published within the last fifteen years. Obviously that leads to a presentism that is kind of horrifying for many of us, in the idea that children would never read the same books as their parents, that you wouldn’t be learning about Japanese internment, you wouldn’t be reading The Diary of Anne Frank. Or, if you were, you would only be reading about it through a very presentist sort of perspective. But to your point, Dan, the Canadian publishing industry could not replenish a library every fifteen years, especially a children’s library. It would leave us much more dependent on American content, and we will lose so much. It’s kind of mind-boggling in its naivete to assume we can simply replenish libraries every fifteen years.

DW: At one point in the book you explain that censorship confronts us with literature’s opposite, and I wondered if you might say a little bit about what you meant by that.

IW: Well, Dan challenged me to actually describe what I like about literature, which is hard for someone who has tried to make that the centre of his life. But one way that I came to think of it: literature asks us, it leaves us, with questions, it prompts more dialogue. If you read a really great book, you want to talk about it. You want to talk about it in a book club. When you close the book, you want to Google it. You want to find out what other people have been saying about it. You want to go on Goodreads. My students would go on BookTok, on TikTok or whatever, but the point is that it opens conversations, it spurs more dialogue.

When you really think about the best books, they’re never reducible to a single message. They’re always full of voices, especially novels. Novels are full of voices, they’re never reducible to a single political point, and this I think is censorship’s opposite. Censorship wants to limit something to a single propagandistic message that we can either be for or against. Censorship confronts us with answers, it has all the answers. It closes conversations rather than opening them. So I think that censorship, and the way that it pretends to have all the answers, and the way that it tries to shut people up, is essentially the opposite of what I love about literature and what I think draws us to literature itself.

DW: Is there a difference between freedom of expression and freedom, or the right, to read? I mean, is there any tension there? This is just a question I was thinking about this evening; we didn’t really talk about that too much while editing the essay, but do they entail different rights or different responsibilities?

IW: I think they are two versions of the same right, and I’ll explain what I mean by that. What I found hard to articulate to that school principal is why I find book banning so offensive. Why do I find it so personally offensive? And undemocratic, in fact. And also illiberal, which is maybe something else. If freedom means anything in our society, it means the freedom to cultivate our own minds, to think what we want to think, to determine the course of our thoughts and our education, and all that is tied in with what we read. And book banning and censorship are not only about deciding what you’re allowed to read, but about deciding what you’re allowed to think, and what kind of a mind you’re allowed to cultivate for yourself. Which is such a profoundly illiberal idea, that someone would interfere with the process in which you are cultivating your own mind.

I think that is a profoundly problematic idea and is what book banners and censors are trying to do. But I think it relates to your point, Dan, about freedom of expression. Because why do we have freedom of expression in our society? It’s not only because you have the right to think and speak what is on your mind. It’s about my right to hear it. And that, I think, makes it complementary to your point about the right to read.

DW: We are all gathered here in a bookstore—let’s assume we all value books. I, as a publisher, as a bookseller, as a reader, have made a very large commitment to literature and books as part of my life. And yet, I’ve been struggling with a contradiction of sorts that I’m hoping you can help me with. I still wonder why it is that at a time that books—for some people, present company excluded—have never seemed less central to the average person’s life, when people have so much access to so much else via the internet, when information has never seemed more free . . . whatever that means. Why, at this moment in time, has the effort to ban books become so increasingly common?

IW: I have to push back on one point, because I don’t think the internet is particularly free. Maybe we can talk more about that in a second, but here’s the statistic that sent chills up my spine and we’ll see if it has the same effect on you. There’s something called the American Time Use Survey that is done by the Department of Labor. Essentially they look at how many minutes per day Americans—it’s an American survey—spend on any given thing. It turns out, and they break this down by every demographic and age and so on, for students, so people between the ages of fifteen and nineteen, the average American spends 9 minutes a day reading and about 4 to 4.5 hours on their smartphones. So, to your point, why is it at this moment where students, high school students, are spending about 9 minutes a day reading for pleasure, are we that worked up about what it is they’re reading? When for a third of their waking lives they are on TikTok or they are on social media and we have no control over—well, most of us—have no control over what our children are doing on those things?

I think there’s something compensatory going on. In a sense that it’s precisely because we have no control. It’s so ephemeral, what kids are experiencing online. You see something that may offend or bother you: it’s there one minute and it’s gone the next. Where do you go if you’re upset by something that you see, where do you protest? Well, people think they’ve found an answer in books because there’s somewhere, there’s a library, there’s a physical place that they can go. They feel like they can exert some kind of control, right? If you’re the sort of person that thinks that LGBTQ literature is going to indoctrinate your child, there’s very little you can do about the online world. But you can go to your children’s school and make a stink about it and pull a book or two from the shelves.

Even if this might seem absurd on its face, as if it could actually work, we need to think about how censorship is working. It’s working in a couple of different ways. It might not work in the sense that it might not be preventing your children from actually accessing that material, which, yes, they will find online. But it might work by keeping it out of their hands at an impressionable life stage. Or, it might work as a way of bringing a political community together to say “We don’t stand for this sort of thing.” In other words it allows for a community to congeal against a scapegoat. That’s another kind of work that censorship is doing. I think that regardless of where you are on the political spectrum, be it left or right, there is a bad habit of thinking about libraries as microcosms of society and books as levers. Where if we want to make society a little more of this or a little less that, the way we’ll go about this is by pulling this book, pulling that book, and that’s going to exert some sort of change on society.

As John Milton recognized over four hundred years ago, bad ideas can spread perfectly easily without books. And they do.

DW: There is an element of symbolic violence in how a lot of people approach book banning. But you brought up Milton, which leads right into my next questions. One of the most interesting and best parts of this book is a survey of at least two thousand years of censorship, from the Romans through Milton and right up to the great twentieth-century censorship trials of Joyce and Lady Chatterley’s Lover and others. I love Milton’s argument that if you put truth and falsehood out there in the world, truth will win out. I am less certain, at this moment in time, still, that that may be true. Milton was saying that relatively shortly after the printing press and the rise of literacy and books as a new technology. We’re now in a new era faced by a new technology that is changing our relationship to truth. And I’m less and less certain as I look at the world, especially at this particular moment, that truth will win out against falsehood. So I guess I’m looking for assurance more than anything at all? That maybe the classic Miltonian arguments still have relevance? Help me.

IW: Well I’m going to be the really pedantic and annoying English professor and say we should turn back to the text. Because what Milton actually says is “Whoever knew, in a free and open encounter, truth to be submerged by falsehood.” But the key part of the phrase is in a free and open encounter, whoever knew truth to be beat by a falsehood. So, Milton is saying if you just let truth and falsehood fight it out, truth will rise to the top. It’s an inspiring idea, and Dan doesn’t believe in it.

DW: I’m just concerned!

IW: But to me the key part of that phrase in the context of social media is “a free and open encounter.” Because I don’t believe that our social media algorithms constitute a free and open encounter. I think that those algorithms are driving certain kinds of content to the top and that what constitutes truth on the internet is certainly not what John Milton would consider truth, and maybe you too.

But, okay, one more thought to leave you with on this is that in the heat of the covid misinformation fever, someone—and I think it was someone in the Biden administration—decided that the lab leak theory was racist and nonsense and was misinformation and it shouldn’t be on Twitter. And I’m not particularly educated on any of this but I do know that the working theory the FBI now has is something along the lines of the lab leak theory. And so, the idea is that if we censor this, we get it wrong. And this is part of what makes censorship so insidious. We get it wrong, and we get it wrong so often that I would err on letting truth and falsehood battle it out even if it’s not a free and open encounter.

DW: I’ll just ask one more question. Given what we’re facing, how can we future-proof our freedom to read and our freedom of expression?

IW: Funding libraries, funding librarians, giving them our full support. Defending our librarians so that they can defend our intellectual freedom, ensuring that there are librarians in schools, ensuring that the schools are properly funded. So many schools these days don’t have a proper school librarian, they’re just not funded. The school libraries aren’t getting the funding that they need, the public libraries aren’t getting the funding that they need, and if you don’t have someone there who knows the collection, who can safeguard it, who knows why books were selected in the first place, you lose the advocate for the library. I think that would be one big thing.

But I think that also we need to get over our trepidation around defending expressive freedom. I consider myself a person of the left, and people of my political orientation have largely given up on free expression, and especially on free speech. Because that has become such a toxic phrase for so many people because of right-wing demagogues who have taken it up. Or you will hear the argument that free speech has never applied to some groups, which is true. That if you look at the history, which I do in this book, that there has been persecution of gay and lesbian and queer bookstores and queer writers and queer presses all throughout history and well into the 1990s. In Canada! So people will say, well there’s never been free speech, there’s never been freedom of expression, this is a hypocritical idea! And my point is that just because there has not been a golden age of free expression does not mean that we can give up on the ideal of free expression, because once we do that we are in serious trouble. And maybe that’s where I would leave that.

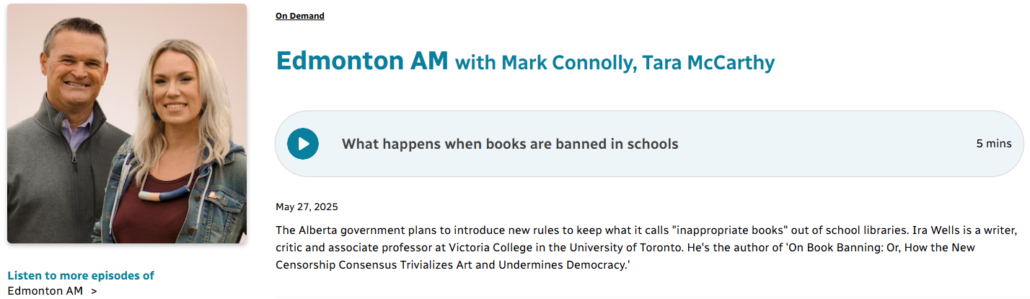

In good publicity news:

- The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk has been shortlisted for the RSL Christopher Bland Prize for debut writers over fifty.

- Elaine Feeney, author of Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way was interviewed about the book in Image.

- Mark Kingwell, author of Question Authority, was interviewed in the University of Toronto’s faculty news.

- On Oil by Don Gillmor was reviewed in Resilience: “Informative and engaging . . . wonderfully captures the gritty realities of life on the rigs and the frenetic energy of oil boomtowns like those in Alberta.”

- A Way to Be Happy by Caroline Adderson was featured in That Shakespearean Rag’s 31 Days of Stories 2025.