The Bibliophile: History is never truly in the past

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

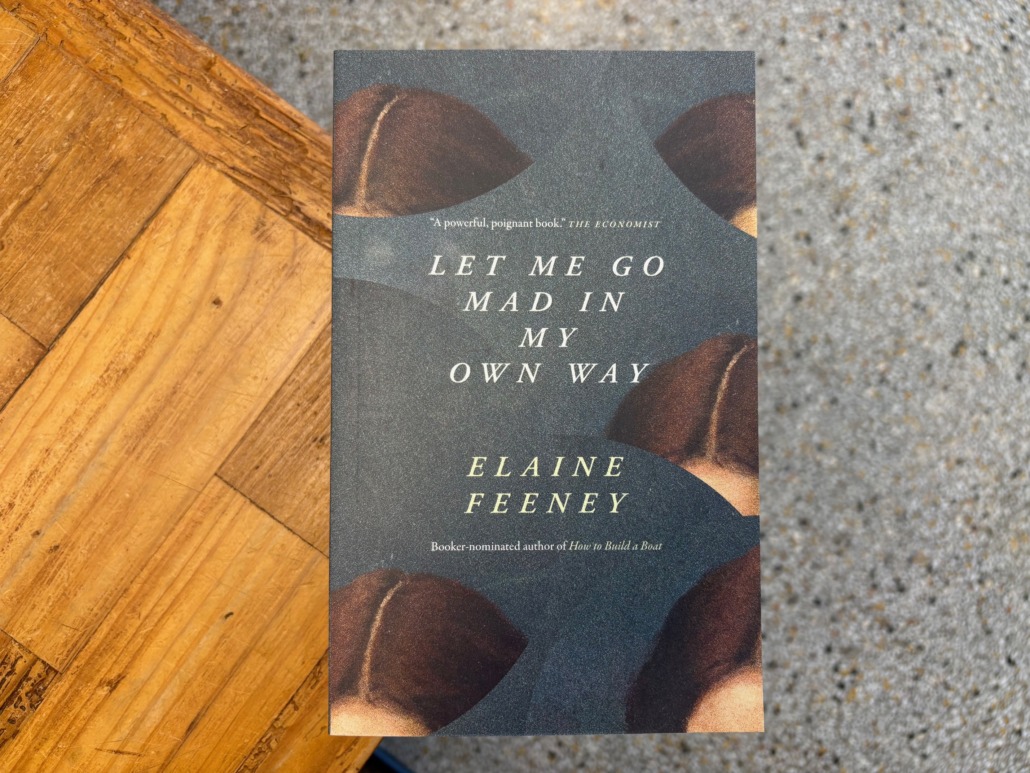

Elaine Feeney’s latest novel, Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way, which comes out next week, has been called her most ambitious. And not just by me. It is about many things: colonialism, tradwives, inherited trauma and shame, the politics of the domestic space, the end of love and a second chance at it. The novel follows an Irish woman named Claire who returns to her family home after many years in England. Her parents have recently died. Her long-term relationship ended. She’s alone and spiraling. So she does what most of us do these days: go online and admire those leading perfectly curated lives. And like the best of us, she takes it too far.

What I loved most about it is how the story unfolds, its structure (“baggy, complex” and “hugely satisfying” as Barney Norris in the Guardian said of it in his review), with a narrative that shifts back and forth across time to show us Claire’s past and how the effects of the violence inflicted on her family echoes down the line—and how she tries to change. It’s almost like a sociological approach to literature, telling a story about the institution of repression in Ireland and its connections to modern tradwifery.

It has been great seeing the response to the novel so far, and how the story resonates. It was even included in the inaugural Booksellers’ List from the Canadian Independent Booksellers Association, making it one of the top 20 books of the fall season as voted on by independent Canadian booksellers. Thank you to CIBA and all the booksellers who voted for it.

And if you’re into bookish events, Elaine will be visiting North America later this month for readings and conversations in Vancouver, Ottawa, Connecticut, and New York. Stop by if you can.

And now what you’ve all been waiting for: the interview. I had a chance to ask Elaine a few questions over email. Read on if you’d like to know her thoughts on her book.

All my best,

Ahmed

Publicist

A Biblioasis Interview with Elaine Feeney

Can you tell me a bit about yourself and how this book came about?

I live in the west of Ireland in a 1970s bungalow surrounded by fields. It’s one of those Bungalow Bliss houses built from Jack Fitzsimons’ guide back in the 1970’s, this was popular in Ireland where these houses were usually on family land next to the “home house”—a small turn of century cottage that was pretty much just a big kitchen and a loft. Those spaces, and their complicated history, really inspired Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way.

The novel follows the O’Connor family from the west of Ireland, the Black and Tans era right up to the slightly surreal world of tradwife influencers today. I’ve always been drawn to the political power of ordinary domestic spaces, especially the Irish kitchen, which holds so much hidden history and tension and sadness (violence) in Ireland.

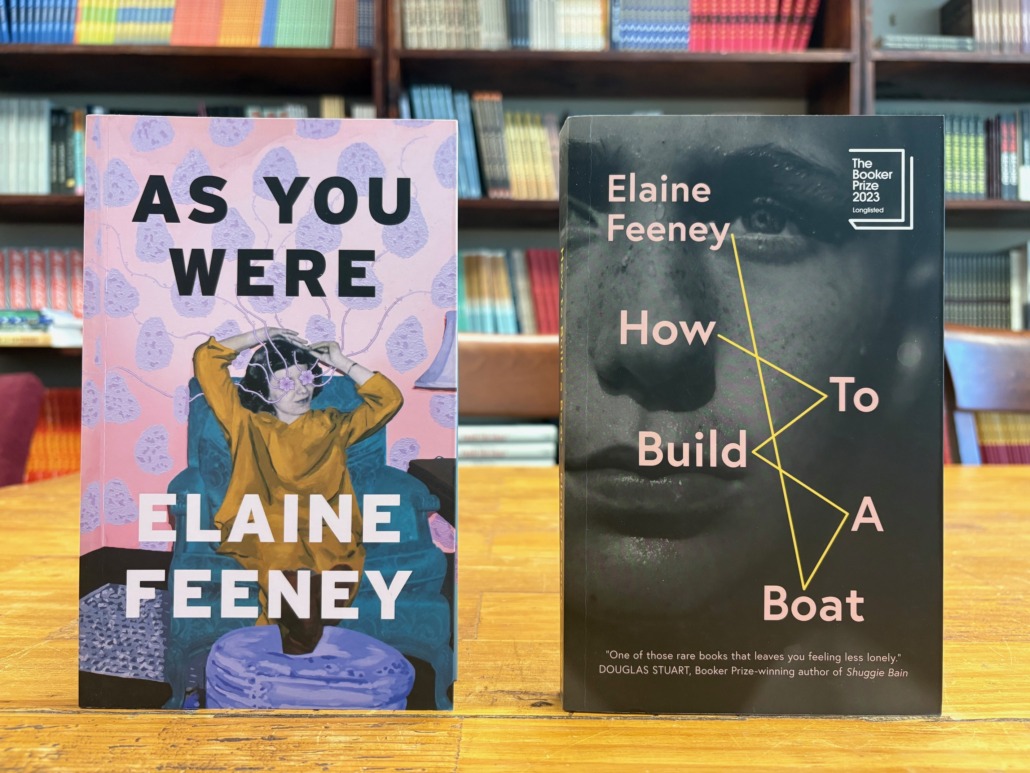

You’ve said previously that you see your three novels so far as examining different institutions: As You Were looked at the hospital, How to Build a Boat looked at the school, and now Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way explores the home/the kitchen. Why the home this time, and what draws you to institutions?

The kitchen has always fascinated me. In Ireland, it’s never just been about cooking or comfort—it’s where history happened. The Black and Tans terrorised people in their kitchens and I really wanted to try to write about this in tandem with Ireland’s dire history of its treatment of women post colonisation: Women were judged, removed, and incarcerated based on what happened within those four walls. It’s been a space of ceremony, loss, survival, and control. I have worked a lot with the long history of institutions in Ireland, and the kitchen seems the most political.

Across my books, I keep coming back to places where care and coercion live side by side. Hospitals, schools, homes—they’re all institutions that are supposed to help, but have historically often end up judging or punishing people instead.

The novel starts with a quote by Annie Ernaux about shame. What role does shame play in the family and the story?

Shame runs deep through the O’Connors’ story. After Irish independence, land ownership became a symbol of respectability and survival. Families clung to that image, and women were made the moral gatekeepers. A spotless house, well-behaved kids, clean laundry—it all reflected on the family’s name. This fascinates me with the rise again of fascism and tradwifery.

Claire, the oldest daughter in the novel, inherits not just her family’s bungalow, but the silence, secrets, and expectations that come with it. The shame of what happened to her mother weighs on her heavily. It becomes this silent, suffocating burden that shapes her actions and her grief.

Claire and her brothers also grieve their parents very differently. What were you trying to show with that?

I wanted to show how siblings experience family history and loss in very different ways. Claire retreats into obsessive domestic rituals to avoid facing her grief and the painful truth of her mother’s death, while her brother Conor carries the family’s legacy in a more external way.

The family is haunted not just by recent grief, but by the trauma of a century of violence, loss, and silence. In Ireland, history has a habit of lingering at the kitchen table, and for the O’Connors that’s definitely true.

Claire turns to a tradwife influencer as a way of coping, which on the surface seems to help her. Where did that idea come from?

It came from my own doom-scrolling, honestly! I kept coming across these soft-spoken, perfect women on Instagram or TikTok, arranging lemons or lighting candles in perfectly curated kitchens while the world burned outside. It fascinated (and unsettled) me. Was it harmless escapism or a soft return to old-fashioned control of women’s roles?

For Claire, following “Kelly Purchase”—my fictional tradwife influencer—isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about desperately trying to impose control over a life that feels completely out of control. It gives her temporary comfort but ultimately isolates her even more.

I love how the novel is structured, moving back and forth across time. Why did you decide to shape it that way?

I wanted it to feel like the piecing together an old family heirloom that’s been damaged or lost over time. Claire’s mind is fragmented, disoriented by grief and avoidance, so the structure mirrors that. It is also very much about the juxtaposition of banality and brutality. (The present in tandem with the future).

In a way, it’s also how so many Irish family histories are passed down—in fragments, in silences, and in stories half-told around the kitchen table. The shifting timelines let me explore how unresolved trauma and silence can distort identity and memory.

Is there anything you hope people take away after reading the novel?

I hope people think about what domestic order hides as well as what it provides. The Irish kitchen has been a place of warmth and nourishment, yes—but also of judgement, punishment, and even violence.

This tradwife trend might seem harmless on the surface, but I wanted to explore how it risks reinforcing systems we’ve fought hard to dismantle. Claire’s journey shows how dangerous it can be to seek safety through compliance and control.

Seamus Heaney said, “Whatever you say, say nothing,” but I wanted this novel to say something: that history is never truly in the past, and silence can become a prison.

In good publicity news:

- Self Care by Russell Smith was featured twice in the Globe and Mail:

- Reviewed by Emily M. Keeler: “Smith’s bleak, horny comedy holds up a funhouse mirror to an aspect of the human condition that feels unique but has always endured . . . There is an undeniably stylish brutality to his portrait of desperately lonely urbanites; when it hits you, you just might laugh.”

- Mentioned in an op-ed on satire by Mark Kingwell.

- Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet appeared in several outlets this week:

- Reviewed in The Scotsman: “Elegant, eerie . . . Perhaps the most impressive feature of the novella is the sense of simmering . . . Macrae Burnet conjures an atmosphere of suppression.”

- Reviewed in The Book Beat.

- Graeme Macrae Burnet was interviewed on The Scots Whay Hae! Podcast.

- Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers by Marcello Di Cintio was featured in The Scene’s article on Calgary literature.

- On Book Banning by Ira Wells was mentioned in Kirkus Reviews’ article, “Book Banning Has Always Been With Us.”

- On Oil by Don Gillmor was reviewed in Alberta Views: “A short, incisive, at times rollicking book.”

- Seth’s 2025 Christmas Ghost Stories were reviewed in The Book Beat: “Each story, from cover to inside decorations . . . sets the scene and mood, while never giving anything away: They’re the creaky door that invites you inside, the things bumped into in the night.”