The Bibliophile: Knowing, searching, hunting

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

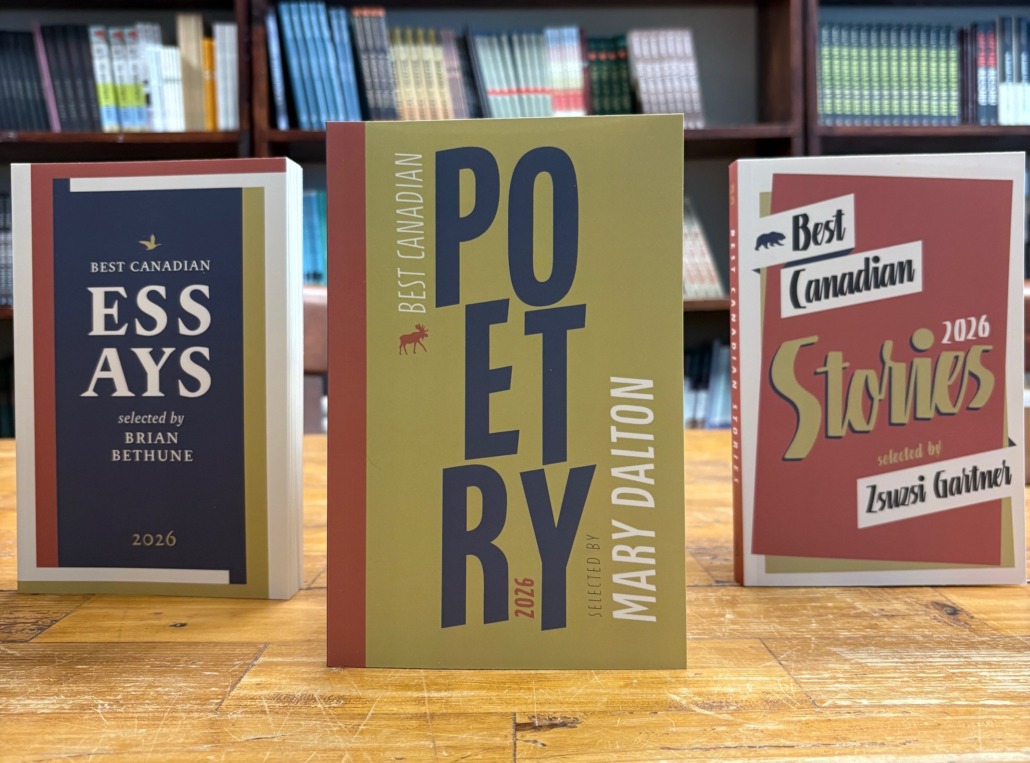

Excerpts from the introductions to the Best Canadian Series 2026

It’s always been a pleasure of mine to help organize and assist with the annual Best Canadian Essays, Best Canadian Poetry, and Best Canadian Stories anthologies, and this year has been no different.

Our editors for the latest editions—Brian Bethune, Mary Dalton, and Zsuzsi Gartner—have all shown such enthusiasm and care during the selections for these anthologies (revisit our contributor announcement), and in the months since, through production and publicity, as we head towards publication next Tuesday, November 18.

On that note, we’d also like to highlight the various launches happening across Canada for each book. For those in the area, we hope you’ll join our contributors and editors in celebrating great Canadian literature and poetry:

- Best Canadian Stories in Vancouver (Nov 18 at 6:30PM)

- Best Canadian Poetry in Toronto (Nov 19 at 6:30PM)

- Best Canadian Stories in Montreal (Nov 24 at 7PM)

- Best Canadian Stories in Toronto (Nov 26 at 7PM)

- Best Canadian Poetry in St. John’s (Nov 30 at 7:30PM)

- A combined Best Canadian Poetry 2025/2026 event in Vancouver (Dec 11 at 7PM)

- Best Canadian Essays in Toronto (Jan 2026: time and date TBA!)

In today’s Bibliophile, we’d like to present a few brief excerpts from the introductions, letting each editor share, in their own words, a little of their journeys to finding the poems, essays, and stories that they considered to be the best.

Happy reading to all,

Ashley Van Elswyk

Editorial Assistant

An excerpt from the Introduction to Best Canadian Essays 2026

by Brian Bethune

When Margaret Atwood’s Jimmy, the protagonist of Oryx and Crake, struggles to help a new species of genetically engineered homo sapiens grasp artistic representation, he eventually tells them, “Not real can tell us about real.” Very true, and a neat encapsulation of the ancient borderline between fiction and nonfiction. And then there are essays, literal “attempts” at reality, which put a lie to the whole notion.

Even in eras which appear, in the full blindness of retrospection, to have been rule-bound days, essays were always among the most protean of literary forms. During times of social, cultural, and economic upheaval like our own, which seems determined to replicate Auden’s “low, dishonest decade” of the 1930s at double the pace, essays are slippery indeed. There surely never was an editor of an essay collection who had a good, working definition of what is and is not an essay. Or, for that matter, didn’t introduce their choices without muttering about the genre’s highly permeable edges.

I am honoured to follow that tradition. Some questions about definition are easy to answer. Can there be too much “I” and not enough other perspective in a work for it to be called an essay? No, just no. For all the varied topics in this volume, from childlessness to catfishing to suicide to mourning, to name a few—the most entrancing essays are intensely personal. Exactly as they have been since Michel de Montaigne introduced the modern world’s first essais: he may be discussing such subjects as war horses, inequality, and cannibalism, he tells readers, but “I am myself the matter of my book.”

That barely scratches the surface, though. What about too little “I” and too many thoughts from others—is it an essay or journalism? How much “not real”—composite characters, timelines subject to torque, heavily edited dialogue and the like—is allowable in a piece of “real” writing that can still be called an essay, nonfiction by definition? To which Montaigne once again provides the only answer: que sais-je? In the end, there’s nothing else to do when defining an essay’s boundaries but to channel your inner Potter Stewart, the US Supreme Court justice who simply gave up on identifying obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

This is what I saw in the essays here. Beautiful writing, acute observation, thought-provoking arguments. And a deep interiority, a kind of personal revelation, sometimes overt, sometimes inadvertent, at times compellingly ambiguous. Sometimes, “real” presents the same human uncertainty and possibility “not real” does.

An excerpt from the Introduction to Best Canadian Poetry 2026

by Mary Dalton

The Anthologist as Star-Nosed Mole

Dear Reader, in making your star-nosed way through this anthology, looking for “something written” (to echo the ideal reader of M. W. Miller’s poem), you will likely make observations and linkages other than my own. Think of the following account as one side of a conversation with you. Reading anthologies myself over the years I’ve developed a habit of leaping headlong into the works assembled; afterwards I settle comfortably into the introduction, eager to engage with the anthologist’s commentary, aware that it might send me back to the poems with some new questions, or some new perspective. Maybe that method will work for you, too?

*

Let me tell you about the star-nosed mole. It’s a curious creature, one I’ve come to associate with the process of searching out the energies pulsing in a genuine poem, whether one is maker or reader. The star-nosed mole spends most of its time in damp underground tunnels. It goes by touching, feeling its way along, navigating by means of the twenty-two fleshy tentacles (the star) at the end of its snout. Those tentacles have over 100,000 nerve fibres; the star-nosed mole has the most sensitive touch organs of any known mammal. Its nose has been called “the nose that sees.” Constantly on the move in its search for food, it is a voracious eater, needing to consume 50 percent of its body weight every day. According to The Guinness Book of Records, it is, among the mammals, the fastest eater on earth.

There’s a headlong, unwilled quality to the activity of the star-nosed mole, a blind searching quality that seems to me akin to the energies operating in the creating of a poem, as well as in the process of discovery involved in reading a good poem. When Dennis Lee, in his essay “Cadence, Country, Silence,” gives the name cadence to the particular aspect of poetry which he tries to summon forth, he is attempting to describe something similar:

I speak of “hearing” cadence, but the sensation isn’t auditory. It’s more like sensing a constantly changing tremor with your body: a play of movement and stress, torsion and flex—as with the kinaesthetic perception of the muscles.

In my reading for Best Canadian Poetry 2026 I quested like the star-nosed mole, snout aquiver for the vital pulse. I aimed to read without program, without preference for particular poetics, region, gender, age, or ethnicity—not with the territorial sweep of the eye but sniffing and snuffling along for the spoor of the genuine.

There were certain touchstones, such as Edward Hirsch’s observation that “the lyric poem exists somewhere in the region—the register—between speech and song.” As well, the myriad manners in which form may fuse with content became apparent in the course of my explorations. The poems which distinguished themselves drew in a variety of ways upon the range of resources available to the poet: among them line- and stanza-shaping, image, figure, and voice.

There is, of course, a variety of themes and types of poems. Some of the types and techniques to be found are: ghazal; ode; monologue; catalogue poems, prose poems; dream narratives; pieces inspired by diary format and online comments format; pieces drawing on vernacular and dialogue. A surreal element operates in several poems, as does humour, often of a wryly ironic sort. The dominant mode is free verse, with its music derived from chains of consonance and assonance. In some instances, anaphora drives the rhythm. The couplet, that wily stanza with its capacity to evoke now confinement and now a ramped-up surging energy, is a frequent structural device.

At this point, looking back over the terrain of the gathering I’ve made, I’m feeling my way among the poems once again, in a mole-like sensing of the contours of the collection—and recognizing again the truth of Adam Sol’s observation, made in his How A Poem Moves: A Field Guide for Readers of Poetry, that this is a golden age for the art of poetry.

An excerpt from the Introduction to Best Canadian Stories 2026

by Zsuzsi Gartner

Once upon a time, a short-story hunter tasked with seeking out the most wonderful stories in the land from the previous year found herself in a burning boreal forest; in Ceylon before Sri Lanka was Sri Lanka; inside a computer game in eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twenty-first-century Quebec; on a freezing mountaintop in Tasmania; in a sweltering monastery in Mexico; and on a barren, unnamed moon. The story hunter watched a woman fall from an opera-theatre balcony, waited for a bull moose behind a pine-beetle blind, and partook of an unconventional Christmas feast. She stalked stories with tranquilizer darts and with a butterfly net, as some stories were as fierce as eight-year-old girls, others as elusive as the scent of moon dust. She hunched next to mountain streams scooping stories by hand like a grizzly scoops salmon, tossing back the fry too undeveloped yet to satisfy her vast appetites.

Many of these marvels were not easy to find, hidden as they were amidst the forests of sameness and swamplands of meh. The cities and suburbs and ex-urbs hid stories as well. The story hunter donned mufti and went knocking door to door to find the stories inside houses where the air was crisped to sixty-four degrees while temperatures blistered outside, houses where detoxing teens oozed drugs through their pores, houses divided into apartments where the online world was more satisfying than anything IRL, and apartments in a nineteenth-century heritage building set ablaze.

Like the naturalists and scientific explorers of the Victorian era, the story hunter discovered new lexicons: the ciphers of amateur cyber cryptographers, the close parsing of CNN.com and NYT required of aspirational newcomers to Manhattan, the deceptively simple language of gaming commands, the non-linear communication style of the Intergalactic Federation of Research Camaraderie, the coded meanings of emojis, and the lingua franca of children wielding their otherworldly power at the beach: Boomshaka. Lingwalla. Boomwalla!

Boomwalla, indeed! The story hunter had tumbled down a rabbit hole and was surrounded by an eclectic array of stories all deserving her full attention, like Alice in the midst of her furred and feathered coterie. And like the Dodo after the mad Caucus-race, the story hunter determined that all were winners and all must have prizes. She hopes the authors will accept these accolades in lieu of sugary confections and a thimble.

In other good publicity news:

- Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet was reviewed in the Chicago Tribune: “Burnet has written the novel from a smattering of historical documents described in an afterward, and he has brewed a powerful spell imagining the darkness surrounding these events . . . For the right reader, Benbecula will be a powerful experience.” Burnet was also interviewed about the book in the Scotsman.

- Every Time We Say Goodbye by Ivana Sajko (trans. Mima Simić) was reviewed in the Irish Times: “However grim the subject matter, the writing remains exceptionally good, with long, majestic sentences that curl unpredictably around the subject. This profound novel is superbly translated by Simić.”

- Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc) got a shout-out in the Irish Times: “An intriguing set of essays by a leading Quebec writer who explores the conflicted legacies of William Styron and James Baldwin to reflect on identity politics in the contemporary world.”

- Self Care by Russell Smith was reviewed in the Winnipeg Free Press: “Self Care isn’t just poking fun. It is also, in many ways, deeply sympathetic to its characters, who are struggling with a world very different from the ones their parents grew up in.”

- Heaven and Hell by Jón Kalman Stefánsson was reviewed in roughghosts: “[Heaven and Hell] combines old-fashioned drama with contemporary literary sensibility, a tale of loss and bravery that makes for a truly glorious read.” Its sequel, The Sorrow of Angels was excerpted in Lit Hub.

- Ray Robertson was interviewed about Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars) for the Booked on Rock podcast.

- Big of You by Elise Levine was excerpted in Open Book: “A masterclass from an author that has few equals in the form . . . Full of disarming tenderness, Big of You showcases Levine’s signature brilliance through language and craft.”

- Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers was included in the Hamilton Review of Books’ staff picks list, “What We’re Reading.”