The Bibliophile: To live through a single day

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

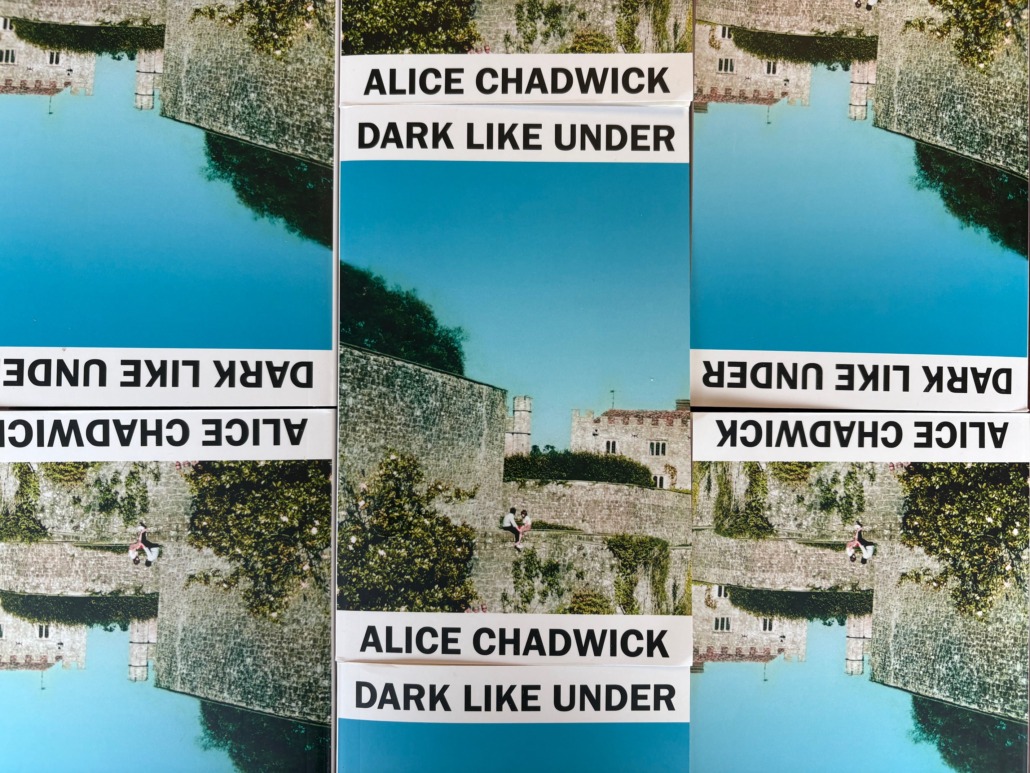

Alice Chadwick’s Dark Like Under follows a large cast of characters—made up of students and teachers at an English secondary school in the 1980s—in the aftermath of a beloved teacher’s sudden death. The premise reminded me of Phillippe Falardeau’s devastating film Monsieur Lazhar, yet Dark Like Under, despite the grief and uncertainty that propel the narrative, feels radically life-giving.

This 336 page novel takes place over the course of a single day, which allows for a heightened attentiveness to the nuances of setting and character. Chadwick really does justice to her characters. I think Pamela Hensley (The Miramichi Reader) gets it right in her recent review:

“Every character is so richly depicted, so expertly drawn with emotional depth and intelligence that we understand not only the individual, but the way each person influences the others and how the town—and the country—has evolved.”

Dark Like Under is the kind of deep, soul-defining book that counters the train chug of reels and the trashiness of beach reads. It allows for immersion in a way that reminds me of summers reading Hardy as a young teenager (before I was expected to work).

Chadwick’s craft is care. This is a beautiful debut novel. It’s also a lovely physical object, with a cover designed by Kate Sinclair, and pages that smell of glue and early summer mornings.

I had the privilege of asking Alice Chadwick a few questions over email, and I’m delighted to share her thoughtful responses here.

Dominique Béchard

Publicist

A Biblioasis Interview with Alice Chadwick

DB: Dark Like Under takes place over the course of a single day. What inspired this decision? Did you encounter any pitfalls (or surprising benefits) to the circadian form? Are there any other circadian books that inspired you?

AC: My novel is set in a school, and I’m fascinated by the ritualistic nature of the school day. The routines are familiar to us all but, from the distance of adulthood, can appear quite strange. Despite their repetitive quality, there are some school days that stand alone, that remain with us throughout life. I wanted to write about one of those days.

The idea of writing a novel based on a school day slotted into the circadian form in a way that felt entirely natural, even irresistible. The single day as a metaphor for the span of a human life has a rich history (I’m thinking of Shakespeare’s sonnet 73—“In me thou see’st the twilight of such day, As after sunset fadeth in the west . . .”). In my novel, the teenage characters are still in the morning of their lives, moving towards the high, bright point; their teachers and parents feel the light dimming as the decades accumulate. I wanted to explore those distinct stages of life and, as we move through the day of the book, the structure itself carries some of that meaning.

Working with the circadian form was tremendously helpful in structuring the novel—I had a beginning and an end, as well as a natural high point. The one-day structure keeps the narrative fresh, the characters in the present moment and the whole thing moving forwards. There is, quite literally, a ticking clock at the heart of the book. Having those things in place allowed me to write very freely. In that sense, I found it unexpectedly liberating and didn’t feel any disadvantages—perhaps those are for readers to point out!

Before I started working on Dark Like Under, I hadn’t realised that a lot of the literature I love best takes a circadian form. Despite the constraints, it’s hugely flexible and seems to inspire innovation. At one end of the scale there is Katherine Mansfield’s short story sequence Prelude, a masterclass in brevity and restraint; at the other, there’s Joyce’s exuberant and encyclopedic Ulysses. My own favourite is Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway; a hundred years after it was written, it still has urgent things to say about female experience in middle age, motherhood and marriage, and about trauma. The spectre of death haunts all these works. Reading them, our appreciation of what it means to live through a single day and through a single life is heightened. They return us to our own daily existence with a sharpened perception of life’s beauty, strangeness and fragile value.

Even though the novel is focused on a single day, this day is perceived polyphonically—through multiple characters. I’m curious to know if this was always going to be the case. Do you have a favourite character, or has that favourite changed over the course of writing the novel?

When I began to write the book, I experimented with the first-person plural perspective—the collective “we.” The whole town has suffered a loss, and I was looking for a way to voice that shared grief. Gradually I realised that individual experiences were equally important, and I shifted to a more polyphonic approach, with each chapter drawing close to one character to observe their particular response (a close third-person perspective). Nevertheless, I wanted to retain something of that initial choral feeling. There is considerable social division in the town of the novel, as in 1980s society more broadly, and it felt important to have a plurality of voices, as far as that was feasible within the school.

Initially, I was writing only from the perspectives of the teenage girls and women. At a certain point, I saw that I needed to open it out further and include those of the boys and men. When I had this thought, I stood up from my desk and walked out of the house—I felt extremely ill-equipped to enter the minds of teenage boys! But it was one of the turning points of the book. A character like Kelly, who had initially functioned as a sort of irritant in the classroom, became quite different when given his own chapters. That took me by surprise—he is now one of my favourite people in the book.

I feel a great deal of tenderness for all my characters, but some were easier to write than others. Nicolas, for example—who is at sea in all the teenage drama and would just like to get on with his homework—flowed out of my pen. He could have taken over the novel! I also love Robin. Her life is far from easy but there is not a speck of self-pity in her. The art teacher, Sue Sharpe, is another character close to my heart. She is not conventionally heroic, or even particularly sympathetic, but she has endured. She attempts to communicate something of genuine value to the kids in her classroom and, despite the disappointments and compromises of her career, still carries the flame of her artistic life.

The 1980s serve as a backdrop for the novel. How much do you think the time period factors into the story? Do you think it would have made for a very different novel if it had been set, say, in the 2000s, or today?

I do think it would be different. The premise—that a teacher could die, and no real explanation be given, no support for staff or children be put in place—is, I hope, unthinkable today. The silence around “difficult” subjects such as death and mental health, gender and sexuality, felt almost total in the 1980s; there was a lack of vocabulary and openness about many things that we discuss more freely and fluently now. That said, some events are inexplicable. People, even those closest to us, can remain mysterious and unknowable. The book, in one sense, is an exploration of that.

The novel is underpinned by the tension between communal experience and social division in a small town. For that reason, the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher, a period of growing inequality and social destabilisation, felt like the right backdrop for the book, even the necessary one. However, the debates of the 1980s remain pressing: how do we look after the most vulnerable in our communities? How do we share the resources of land, money and education?

I also really wanted to capture an “analog” way of being alive that has almost entirely disappeared now. The texture of life was so different in the 80s—the way we passed little handwritten notes around and did all our learning from books; how, if we wanted to phone someone, we had to stand in the hall and use the landline, where the whole family could hear. Photographs were rare; we didn’t walk around with cameras and films were expensive to process. It was a different way of being an individual and of experiencing time; as a teenager you might be alone or bored, isolated or idle, to an extent that is almost impossible now. That said, teenagers are teenagers. The excitement, defiance and uncertainty of those years belong to us all, whichever decade we grew up in.

Dark Like Under is so richly detailed and elaborate. It seems to go against the distracted, content-driven culture we live in. The level of your attentiveness is impressive. What are your writing habits like?

Thank you! One of the things I love in books—and not just books, in painting, photography, cinema too—is the noticing, the observation of small details that are everyday but at the same time surprising and telling. There are many ways of paying attention, but I love an immersive book, one that takes you wholeheartedly into a place, into the lives of its characters, and lets you have a long look around. It’s a slowing down, yes, and in that respect requires a level of close attention, but that, to me, feels generous and nourishing.

But to answer your question: my writing habits are very regular, very workaday. Every morning I get up, make coffee and go outside, often before London has fully woken up. I like to write in the garden, surrounded by my neighbour’s houses, by trees and birds. It’s a small patch of urban Eden! I work in cheap exercise books, which are often covered in soil and smudged by rain, but the work I can do by hand, early in the morning, seems freer and more unexpected than anything I can do on a screen. Later, I do go inside and work at my desk—I like to type things up and edit on my computer. In the late afternoon, I might go for a walk to clear my head, and sometimes I do other (paid) work. Evenings are for reading, and reading is very much part of writing, a crucial part.

I write every day and most days I struggle, but I’ve learnt that these dull, difficult days are necessary. They often herald a breakthrough, a dreamlike period when words finally flow and stray ideas come together.

I’m interested in the title, Dark Like Under. I love the cryptic imagery it inspires. Could you tell us about how you came to it?

The title came to me slowly, I had to wait for it. I’ve had this experience with poetry; it can take a long time for the right words to surface and find an order. I always knew that there would be “dark” in the title, however. In the western tradition, in the Bible or Dante, say, knowledge and goodness are often associated with light and illumination, but some of the most important lessons we need to learn, not to mention things of great mystery, nuance and beauty, come from places of darkness. It’s where ghosts, and Time itself, accumulate—sometimes in a literal sense, in the buried, archeological layers under our feet. The art teacher in the school tries to teach something of this to the kids: to draw a pebble, to describe a human face, requires a sensitivity to the shadows as well as the highlights. There is only so much that light can teach us. But it is, of course, a question of balance, of not being pulled under by the dark.

Have you read anything lately that you’d like to recommend?

I am halfway through Rose Tremain’s 1992 novel, Sacred Country. Told in multiple voices, it’s a portrait of a sleepy, slightly eccentric village and the story of a young girl who discovers, aged six, that she is Martin, not Mary. It’s funny and deeply touching, and I feel as though I’ve left behind friends every time I put it down.

I’ve also just finished James Agee’s A Death in the Family, a novel (as mine is) about a sudden death and how people live through those first hours and days. I now know that it’s a classic of American literature, but I hadn’t heard of it until a bookseller pressed a copy into my hands. I’m grateful that he did.

In good publicity news:

- Mark Bourrie, author of Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, published a new piece on Poilievre in The Walrus.

- Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way by Elaine Feeney was:

- Reviewed in the Irish Star

- Named an RTE Book of the Week: “A masterclass in Irish storytelling.”

- Listed as one of the Economist’s 40 best books published so far this year: “A powerful, poignant book.”

- Reviewed in The Guardian: “Hugely satisfying . . . the novel’s baggy, complex, unfolding structure offers rich rewards.”