The Bibliophile: The Biblioasis Holiday Book Guide (Part III)

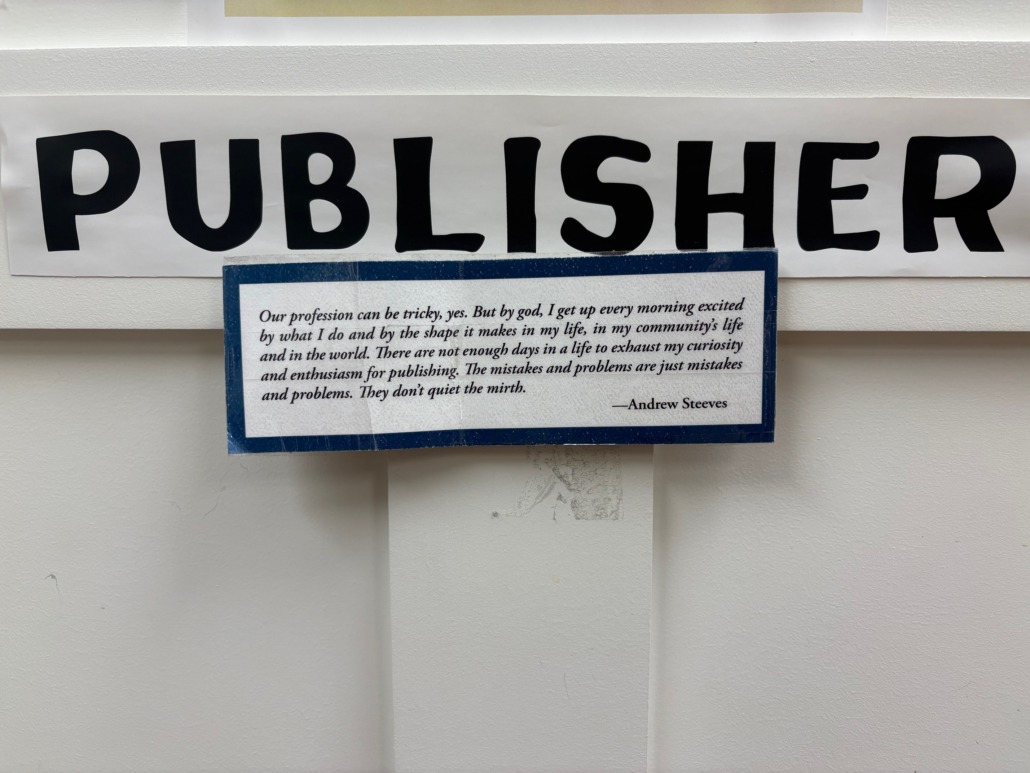

It is almost impossible this year for me to separate the books we’ve made from the manner and condition of their making. Slow learner (the title of my publishing memoir) that I am, 2025 was the year that I learned, or at least finally realized, that publishing will never get easier. It’s also the year I made my peace with that, its problems and frustrations and challenges also giving shape to some of its primary pleasures. I’ve had a sentence or two from Andrew Steeves taped to my door since 2019, sent to me by another publisher at an earlier point of (supposed) crisis, that suggested as much: this was the year I came to understand this more fully.

There’s a question I’ve been thinking about a lot in recent months, as I’ve grappled with the various challenges 2025 brought to the fore, something I hope to write about more in the Bibliophile throughout the coming year if I can find the time (time being the most precious of resources): What is publishing for? I’m not sure it’s a question I asked when I shifted Biblioasis into the publishing sphere twenty-one years ago: that was brought about almost exclusively on the backs of ignorance and ego. For better or for worse, there’s a lot less of both around here these days. There have been moments where I feared I lost the plot a bit, in which I needed to rethink what it is we’re trying to accomplish; but looking at our list over this past year, I no longer worry that this is the case. The plot has perhaps thickened, become more expansive; we’ve learned a lot about what we can do, and what we should; we’ve learned that we can and should expect more of ourselves, and of the books that we publish. And I think this year, with its wide range of titles and subjects, covering history, politics, culture, fiction, poetry, criticism and much else, attests to this. It was the best and worst of years; and yet, still one of the best. I’m grateful for (almost) all of it.

Rather than repeating what others have already highlighted in the earlier installments of this series of Holiday Book Guide posts, I thought I’d focus on half a dozen things not yet discussed, but that also speak to the full range of our publishing commitments, and offer evidence, I hope, for how we’ve grown and developed since those earlier, more ignorant days. If you haven’t already, please do check out the first parts of this series, as there’s some most excellent suggestions to be found therein.

Around this time last year, when it would have been nice to be winding down, the heavy lifting began in earnest on one of the key books of our 2025 publishing year, Mark Bourrie’s Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre. Conceived only six months earlier over coffee in my back yard after a launch, initially as a much shorter Field Note, we worked with its author (and, truth be told, worked its author) through Christmas and the usual holiday break, then through January and early February, to get the book out in advance of the impending election. We’d assumed that we would have until summer or fall 2025 to produce the biography, but events, as they often do in both politics and publishing, conspired against us, forcing us to get the book finished in record time. We learned a lot in the process about this kind of publishing, about politics, and about our own limitations and the costs of pushing so far past them. We were able to get it out a few weeks before the election, and I think it’s fair to say that the book played a big role in the coverage of the ensuing campaign. I was amazed by Mark’s ability to pull it all together, doing a few years of research and writing in under eight months. Elaine Dewar told me that she believed Ripper contributed to Poilievre’s unexpected defeat in the election; whether or not this is true—Poilievre played a very big role in the outcome himself—this type of publishing feels like the kind of thing we have a responsibility to take on, and I’m grateful that I have been able to work with writers like Mark to tackle these kinds of books when they are needed. I expect that there will be more books like it in the future.

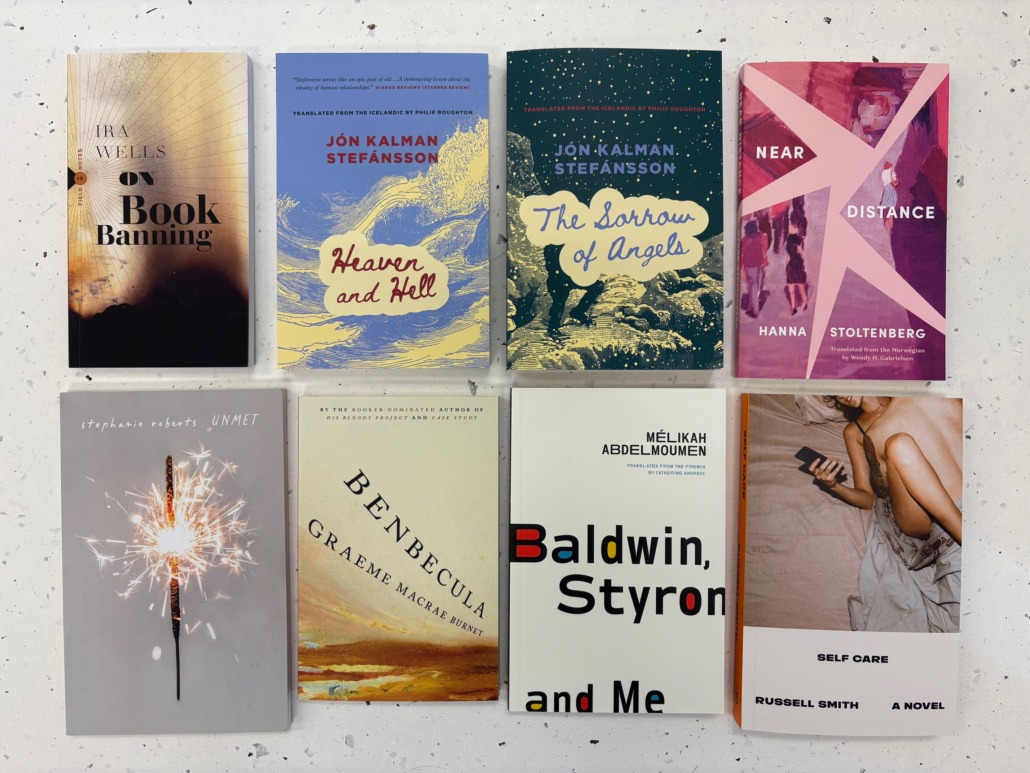

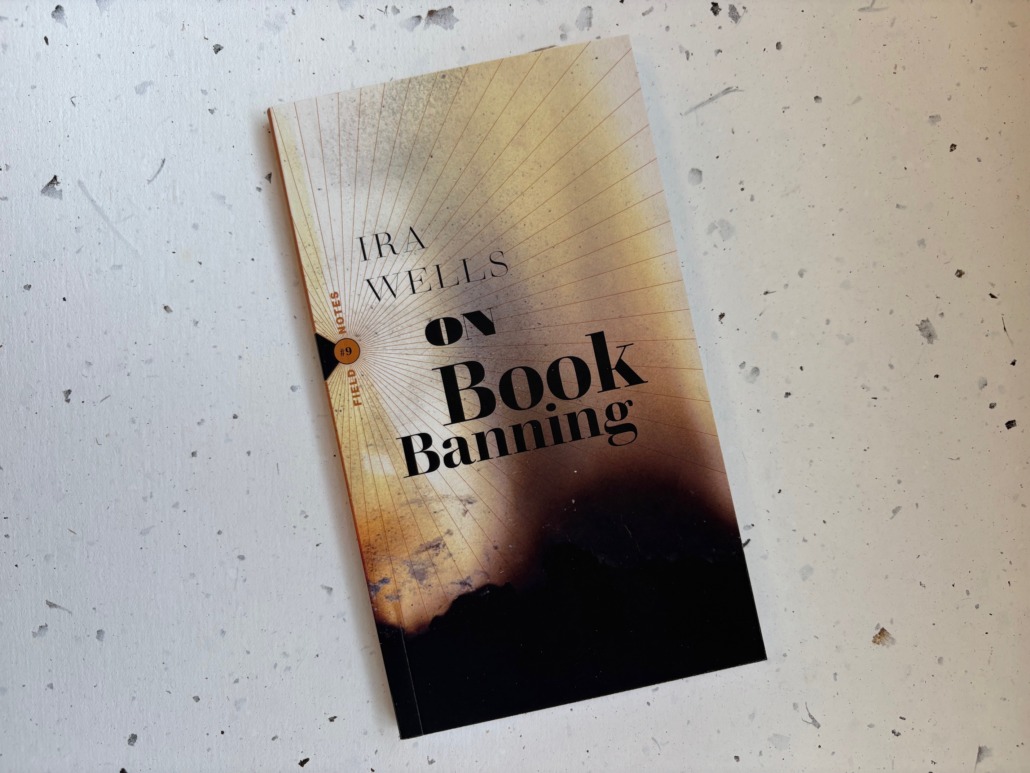

One of the reasons we began the Field Notes series back in 2020 was to try and become more engaged, more responsive and responsible publishers, and in 2025 we published two of my favourite books in the series. Ashley wrote a couple of weeks ago about Ira Wells’s On Book Banning, so I’ll spend a paragraph here on Don Gillmor’s On Oil. I think On Oil is easily one of the most elegant and engaging books in the whole series, a mix of memoir, investigation, and meditation of our tortured relationship with a substance that is pushing the world to the brink of collapse. Don was a roughneck in his university years, and he writes of his experiences in that community with humour, intelligence, and sympathy; but it’s his short precis of the history of oil extraction, its relationship to the evangelical movement in both Canada and the United States, and how early we understood that our oil dependence was contributing to global warming (and how quickly both oil companies and government agencies rushed to cover this up, though they were fully cognizant of the consequences) that makes this book such a revelation, and an essential part in the series. It may not seem to be the most engaging of subjects, and—wherever you are on the political spectrum—you may figure that you know enough already about oil, and where you stand on the issue. Don’s book will challenge your assumptions and entertain in equal measure. It should have made every Best of the Year list out there: it’s certainly on mine.

It is hard to believe that it’s been more than three-and-a-half years since we lost Steven Heighton. I miss him. So it was a consolation this year to be able to bring out his selected stories, Sacred Rage, gathering fifteen stories from across his four collections, and I hope cementing his reputation as one of the best short story writers this country has produced. He told John Metcalf, his editor for both his first two and last two books, before he knew that he was ill, that returning to the short story after years of trying to be a novelist was like returning home, that it was in the story, more than even poetry, that he felt that he’d made his most important contribution to literature. Anyone who reads the stories in Sacred Rage will have a hard time disagreeing with him.

I first conceived of the idea of doing a book on migrant workers and their lives more than a decade ago. The first writer we brought on to tackle the subject, whose family began in the fields as farm workers in the early post-WWII years and who now, a couple of generations later, owned some of the larger greenhouses in the area, retreated from it after talking with his family: the personal costs of writing the book as he intended would have been too great. But it always remained at the back of my mind, and after working with Marcello Di Cintio on Driven a few years ago I knew that I’d found the right person to tackle the migrant project. Marcello brought an incredible curiosity, humanity, and sympathy to his subjects; a willingness to dig deep, to ask uncomfortable questions, and to do the hard investigative work essential to a book like I was proposing. His Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers was everything I hoped it would be, a propulsive, informative, and righteously angry examination of the lives of those often brought to this country to do the work that Canadians don’t want to do.

I’ve worked with Ray Robertson now for seventeen years, since we republished his novel Moody Food in 2008, still one of the best rock and roll novels, to my mind, ever published. It shocked me to realize that Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars) was the eleventh book we’ve done with him over that time, by far the most books we’ve published by any author. Dust picks up where his initial Lives of the Poets (with Guitars) left off, and though there are a few artists without guitars here—James Booker and Nico—that gathered assemblage will still get your foot tapping, and introduce you to artists that you might not otherwise have heard of. My favourite essay in the collection is on the Toronto Rockabilly artist Handsome Ned: I’m looking forward to spending some of the holidays getting better acquainted with his music.

Lastly, we completed our latest installment of our Best Canadian anthologies, and this year’s installments are as good as any that have come before. I’ve long admired Mary Dalton as a poet; she shows, in Best Canadian Poetry, that she’s an equally fine editor. Zsuszi Gartner in Best Canadian Stories has pushed the boundaries of my understanding of what a good short story can do, and I’ve been amazed by and grateful for her enthusiasm and promotional verve: her good work has made this year’s anthology one of our best-selling collections to date. Every year, Best Canadian Essays seems the neglected child of this gathering, which is unfortunate, because it is to my mind, year after year, the most consistently excellent of the three, and this installment is no exception: Brian Bethune has brought together a wonderful gathering of essays covering everything from catfishing and climate change to motherhood and mental health. It’s worth picking up from your local indie the next time you’re in the shop. Or better yet, pick up all three!

There is no Ripper to prepare this holiday, thankfully, even if there is, as always, too much work to do. We’re all looking forward to a much needed break, with family, friends, and good books. If you’re hungry for the latter, you could do worse than picking up a couple of the above, or any of the other choices presented in earlier installments of the Holiday Gift Guide. Thank you for reading, and we wish you a Merry Christmas and a wonderful new year, and we’ll see you in 2026.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

Biblioasis 2026 Subscription Clubs

A few sharp-eyed folks may have already caught a glimpse of this announcement on our socials or website, but we’re pleased to announce that our 2026 Subscription Clubs are now available!

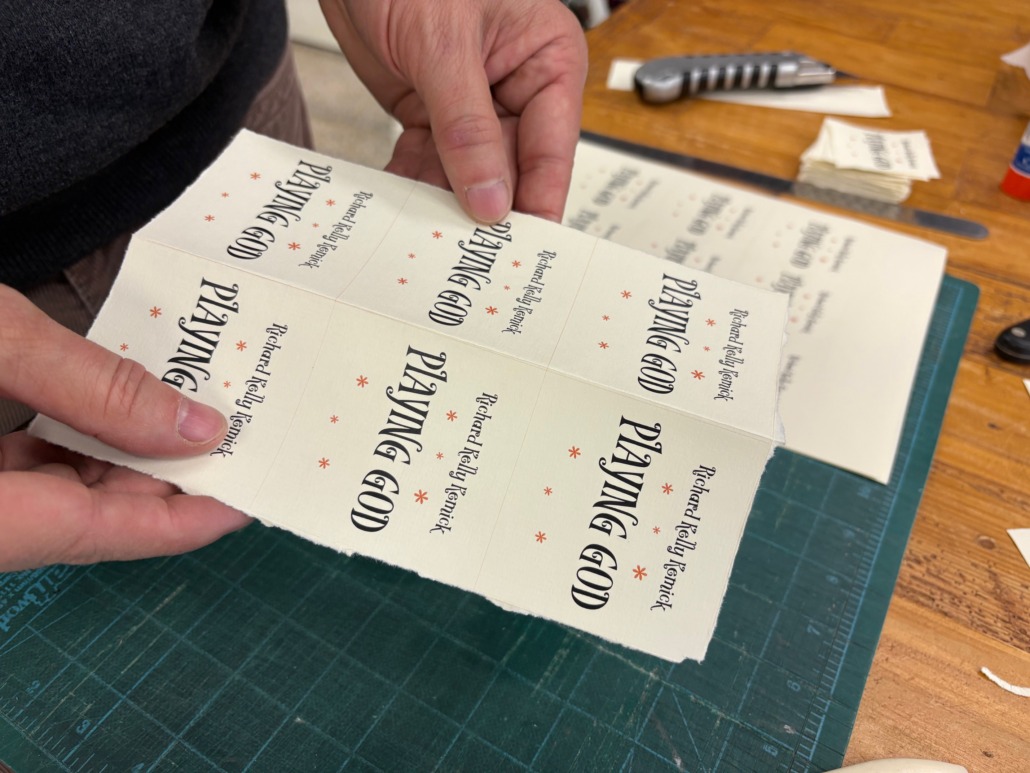

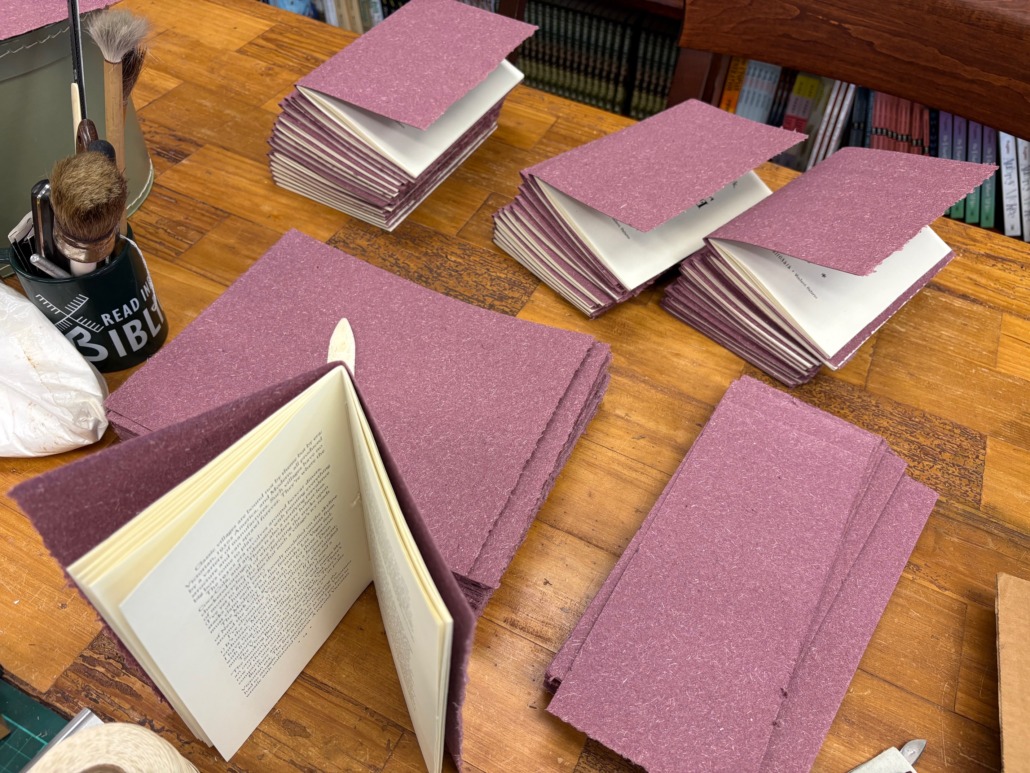

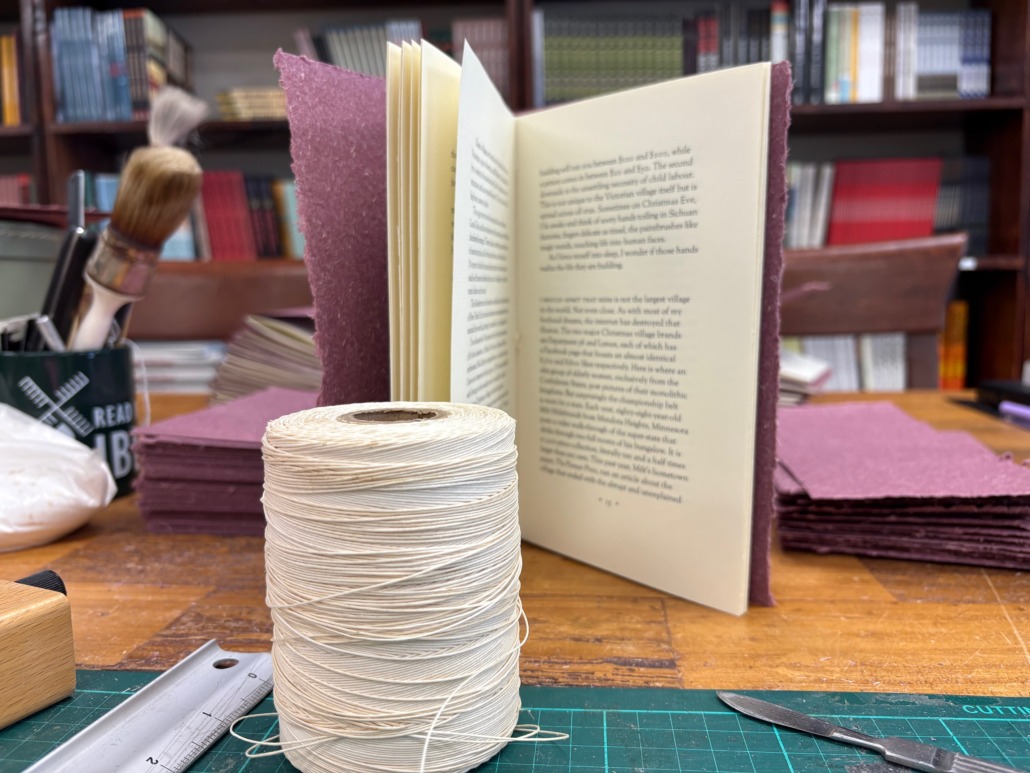

This year, we’re offering bundles for Fiction, Nonfiction, Surprise, Choose-Your-Own, alongside new addition to the line-up: The Limited Editions Club, which features five selected titles, each in a specially-designed series edition, signed by the author.

Every subscription comes with five titles, plus bonus Biblioasis ephemera from buttons to ARCs and more (the Limited Editions Club has a few extra goodies). They make a great gift for your favourite bibliophile, or the perfect treat for yourself to enjoy throughout the year. Whether it’s stories and essays filled with humour, loss, and reconnection; a literary detective novel; an exploration of sports; striking new poetry; or translations from across the globe, you can trust you’ll find a book to add to your shelves.

You can view each subscription club on our website, and in the process, get a sneak peek at what titles we have in store for 2026.

In good publicity news:

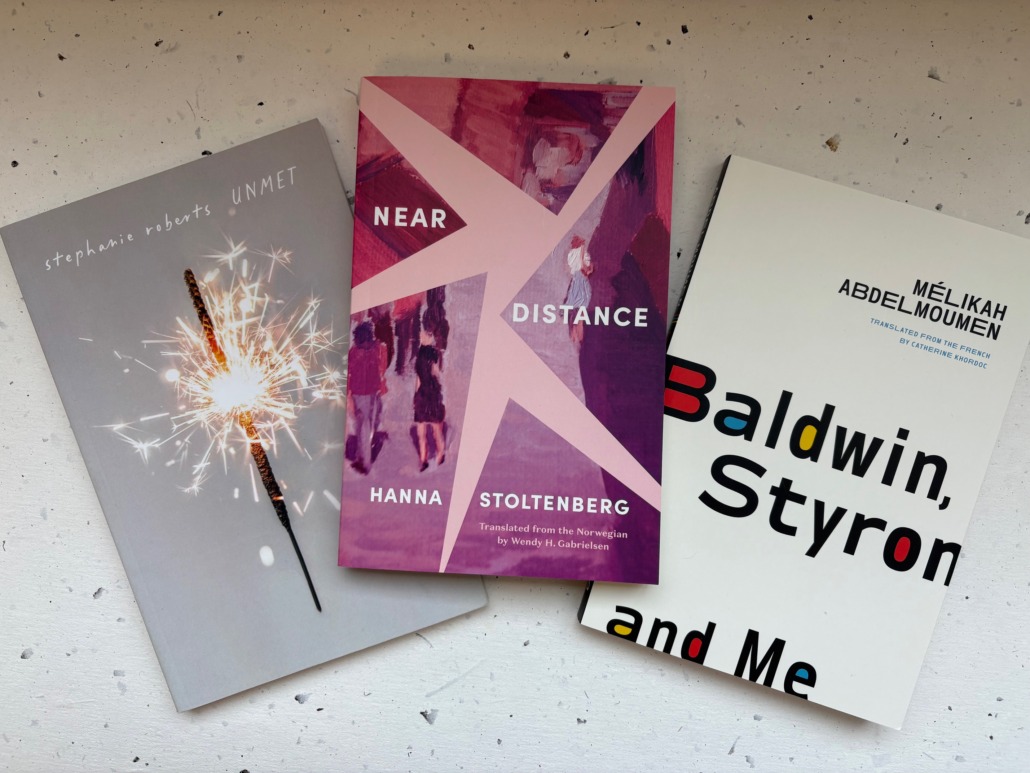

- Near Distance by Hanna Stoltenberg (trans. Wendy H. Gabrielsen) was longlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award’s 2025 Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize!

- On Book Banning by Ira Wells was included in the Winnipeg Free Press’s list of best books of 2025: “A pocket-sized provocation for educators to help arm themselves against those who wish to remove books from libraries.”

- The Passenger Seat by Vijay Khurana was picked as one of London Magazine’s best books of 2025: “Khurana’s glass-cut, rhythmic sentences plunge you into a world of obsessive friendship and insecurity, a game of one-upmanship that feels eerie in its innocence.”

- Sacred Rage by Steven Heighton was reviewed in the Literary Review of Canada: “Formally brilliant, ranging from the hilarious to the heartbreaking . . . if there is any justice in this literary world, Heighton’s legacy will be his love of language, evident on every page.”

- Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers by Marcello Di Cintio was reviewed in the Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm.

- Batool Abu Akleen’s diary entries from Voices of Resistance: Diaries of Genocide were excerpted in The Walrus.

- Who Else in the Dark Headed There by Garth Martens (April 2026) was featured in Publishers Weekly’s Spring 2026 Poetry Preview.