The Bibliophile: An introduction from our new Sales Coordinator

Hello, Bibliophile readers! It’s a pleasure to introduce myself as the new Sales Coordinator here at Biblioasis. This is the last day of my first week of full-time work, most of which I got to spend in the office in Windsor. Toronto is my beloved home base, but I’ve had a great time exploring the city and its environs—including one of the best Turkish bakeries I’ve yet come across in Ontario.

It’s hard to put into words just how exciting it is to have joined the (brilliant) Biblioasis team. Before starting at the press, I was working as a bookseller at the beautiful Flying Books on Queen Street in Toronto, which connected me to a vibrant literary community. I had spent the years between 2019 and 2024 teaching full time at The University of King’s College in Halifax, an experience I found incredibly meaningful, but publishing was my first love. Since as long as I can remember, I’ve had more books than space to accommodate them. Books have accompanied me throughout my life. They have given me a sense of place and rootedness in the midst of many types of transitions.

Sitting in the Biblioasis office with shelves of wonderful titles behind me has been a genuine thrill. There is a lot to learn, but after teaching for so many years, I’m enjoying feeling like a student again, making one discovery after another. Everyone I’ve met so far has been patient, supportive, and welcoming. I’m passionate about our books and I’m looking forward to championing them.

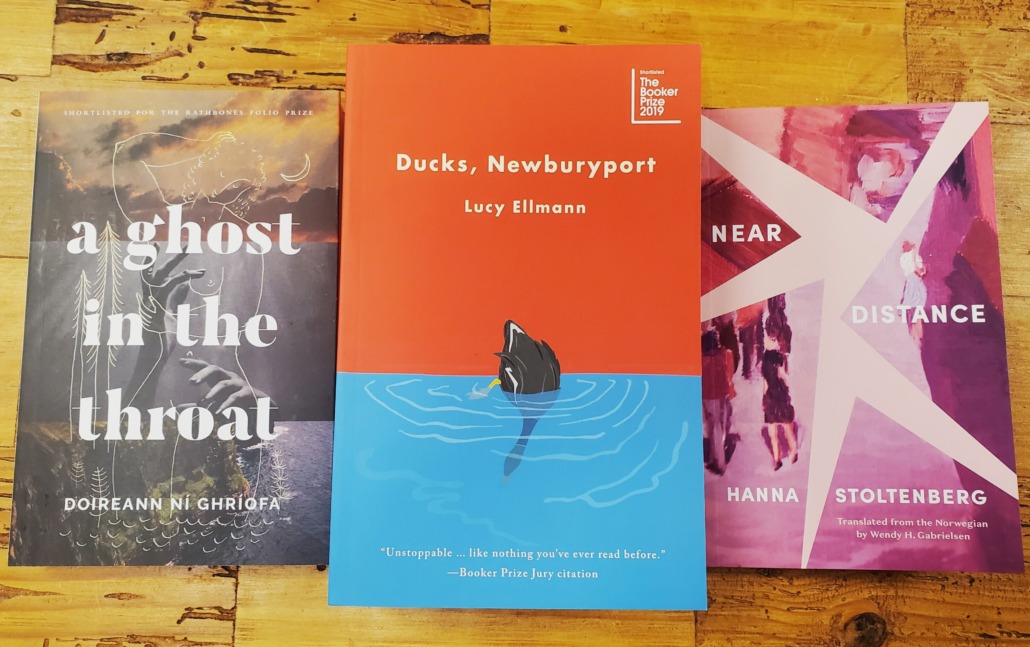

As a bonus, here are some of my favourite Biblioasis titles. Incidentally, they are all works of fiction written from the perspective of mothers: Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport (if you haven’t tackled the tome yet, take this as your sign—it’s more relevant than ever), Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat (one of the most lyrical genre-bending works I’ve come across), and Hanna Stoltenberg’s Near Distance (an unflinching modern take on the mother-daughter relationship that I think Simone de Beauvoir would have loved).

Hilary Ilkay

Sales Coordinator

In other news, Lazer Lederhendler is the fiction winner of the French-American Foundation Prize for his translation of The Hollow Beast! The foundation conducted a short interview with Lazer about his experiences working with Christophe Bernard’s “beast of a novel.” We’re delighted to present it here, ahead of the awards ceremony in New York next week.

Q: What did you enjoy most about translating The Hollow Beast by Christophe Bernard?

Lazer: Problem solving is one of the things I love most about translating good fiction, and I was well served in that department by Christophe’s fabulous beast of a novel. I did a good amount of research on English dialects of Eastern Canada that are comparable to the French spoken on the Gaspé Peninsula, where most of the action is located. This proved to be not the most fruitful avenue, as the linguistic idiosyncrasies of the book are mainly due to Christophe’s unique and highly evocative visual style. In fact, it occurred to me that The Hollow Beast has all the makings of a wonderful graphic novel. So rather than focusing primarily on language equivalencies or approximations, I would picture the characters and scenes in detail and render those images into English (and afterwards, of course, make sure I hadn’t strayed from the original). On the other hand, however, there was the challenge of depicting the evolving speech patterns of the story’s hero, Monty, who starts out quasi-illiterate but through self-education (he carries around a copy of Homer’s Odyssey) progressively acquires a more sophisticated level of French.

Q: You specialize in translating contemporary Quebecois literature. What are some differences you’ve noticed between contemporary French literature in Canada and French literature in France?

Lazer: That’s a huge question, perhaps best left to academics. But one clear difference that does immediately come to mind is this: today, more than ever before, Québécois literature and Québécois culture and language in general are very much creatures of North America, whose references and influences point increasingly south and west rather than to Europe. This is true, at any rate, for most of the writers I’ve translated since the early 2000s — Nicolas Dickner, Catherine Leroux, Perrine Leblanc, et al — who are assuredly representative of contemporary Québécois fiction. Another basic difference worth mentioning is that the literature of France by and large takes the language for granted — ça va de soi. The same can’t be said of Quebec, where the French language has always been a battle field that, as a friend of mine put it, is foregrounded as a constituent part of the landscape.

Q: The French-American Foundation Translation Prize seeks to honor translators and their craft, and recognize the important work they do bringing works of French literature to Anglophone audiences. What does being named a winner for this prize mean to you, and, in your own words, why does a Prize like this matter?

Lazer: Translators are among the unsung artisans of literature endeavouring to carry the words and artistry of writers across the barriers of language and culture. We for the most part labour in the shadows in order to extend the reach and longevity of an author’s works. So it’s always encouraging and gratifying to have one’s efforts as a translator acknowledged and celebrated. What’s more, awards like the FrenchAmerican Foundation’s Translation Prize, spotlight books and writers that otherwise might not get the attention and readership they deserve.

In good publicity news:

- The Passenger Seat by Vijay Khurana was reviewed (again!) in The New York Times: “Structurally ingenious, rendered in unusual and fine colors, buffed to a shine. A perfect debut novel, explicit in its excellence!”

- Vijay Khurana was also interviewed on the podcast Final Draft.

- On Book Banning by Ira Wells was excerpted in Lit Hub.

- Dark Like Under by Alice Chadwick was listed in The Globe and Mail’s “The best of summer books.”

- Alice Chadwick interviewed Alice Chadwick for Debutiful.