Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

In celebration of Black History Month, we’re highlighting our books by Black writers, along with some additional reads. If you’re on the lookout to expand your knowledge in nonfiction, read stories that take you around the world from the Caribbean to Angola, or discover strikingly new poetry, then have a browse through the titles below and find something to add to your reading list—for this month, and beyond.

Ashley Van Elswyk,

Editorial Assistant

***

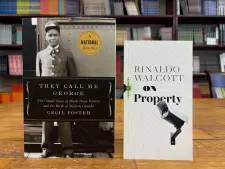

They Call Me George by Cecil Foster, cover designed by Michel Vrana, and On Property by Rinaldo Walcott, designed by Ingrid Paulson.

Nonfiction

They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada by Cecil Foster

Smartly dressed and smiling, Canada’s black train porters were a familiar sight to the average passenger—yet their minority status rendered them politically invisible, second-class in the social imagination that determined who was and who was not considered Canadian. Subjected to grueling shifts and unreasonable standards—a passenger missing his stop was a dismissible offense—the so-called Pullmen of the country’s rail lines were denied secure positions and prohibited from bringing their families to Canada, and it was their struggle against the racist Dominion that laid the groundwork for the multicultural nation we know today. Drawing on the experiences of these influential black Canadians, Cecil Foster’s They Call Me George demonstrates the power of individuals and minority groups in the fight for social justice and shows how a country can change for the better.

On Property by Rinaldo Walcott

That a man can lose his life for passing a fake $20 bill when we know our economies are flush with fake money says something damning about the way we’ve organized society. Yet the intensity of the calls to abolish the police after George Floyd’s death surprised almost everyone. What, exactly, does abolition mean? How did we get here? And what does property have to do with it? In On Property, Rinaldo Walcott explores the long shadow cast by slavery’s afterlife and shows how present-day abolitionists continue the work of their forebears in service of an imaginative, creative philosophy that ensures freedom and equality for all. Thoughtful, wide-ranging, compassionate, and profound, On Property makes an urgent plea for a new ethics of care.

***

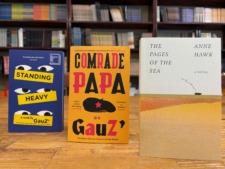

From left to right: Standing Heavy and Comrade Papa by GauZ’ (trans. Frank Wynne), with covers designed by Nathan Burton, and The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk, designed by Kate Sinclair.

Fiction

The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk

On a Caribbean island in the mid-1960s, a young girl copes with the heavy cost of migration.

When her mother emigrates to England to find work, Wheeler and her older sisters are left to live with their aunts and cousins. She spends most days with her cousin Donelle, knocking about their island community. They know they must address their elders properly and change their shoes after church. And during the long, quiet weeks of Lent, when the absent sound of the radio seems to follow them down the road, they look forward to kite season. But Donelle is just a child, too, and though her sisters look after her with varying levels of patience, Wheeler couldn’t feel more alone. Everyone tells her that soon her mother will send for her, but how much longer will it be? And as she does her best to navigate the tensions between her aunts, why does it feel like there’s no one looking out for her at all? A story of sisterhood, secrets, and the sacrifices of love, The Pages of the Sea is a tenderly lyrical portrait of innocence and an intensely moving evocation of what it’s like to be a child left behind.

Standing Heavy by GauZ’ (trans. Frank Wynne)

A funny, fast-paced, and poignant take on Franco-African history, as told through the eyes of three African security guards in Paris.

All over the city, they are watching: Black men paid to stand guard, invisible among the wealthy flâneurs and yet the only ones who truly see. From Les Grands Moulins to a Sephora on the Champs-Élysées, Ferdinand, Ossiri, and Kassoum find their way as undocumented workers amidst political infighting and the ever-changing landscape of immigration policy. Fast-paced and funny, poignant and sharply satirical, Standing Heavy is a searing deconstruction of colonial legacies and capitalist consumption and an unforgettable account of everything that passes under the security guards’ all-seeing eyes.

Comrade Papa by GauZ’ (trans. Frank Wynne)

Mourning the recent deaths of his parents, a young white man in nineteenth-century France joins a colonial expedition attempting to establish trading routes on the Ivory Coast and finds himself caught between factions who disagree on everything—except their shared loathing of the British. A century later, a young Black boy born in Amsterdam gives his account, complete with youthful malapropisms, of his own voyage to the Ivory Coast, and his upbringing by his father, Comrade Papa, who teaches him to always fight “the yolk of capitalism.” In exuberant, ingenious prose, GauZ’ superimposes their intertwined stories, looking across centuries and continents to reveal the long arc of African colonization.

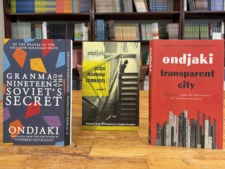

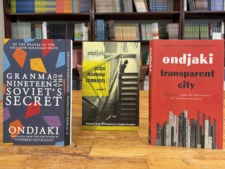

All by by Ondjaki, trans. Stephen Henighan: Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret (designed by Kate Hargreaves), Good Morning Comrades, and Transparent City (designed by Zoe Norvell).

Good Morning Comrades by Ondjaki (trans. Stephen Henighan)

Luanda, Angola, 1990. Ndalu is a normal twelve-year old boy in an extraordinary time and place. Like his friends, he enjoys laughing at his teachers, avoiding homework and telling tall tales. But Ndalu’s teachers are Cuban, his homework assignments include writing essays on the role of the workers and peasants, and the tall tales he and his friends tell are about a criminal gang called Empty Crate which specializes in attacking schools. Ndalu is mystified by the family servant, Comrade Antonio, who thinks that Angola worked better when it was a colony of Portugal, and by his Aunt Dada, who lives in Portugal and doesn’t know what a ration card is. In a charming voice that is completely original, Good Morning Comrades tells the story of a group of friends who create a perfect childhood in a revolutionary socialist country fighting a bitter war. But the world is changing around these children, and like all childhood’s Ndalu’s cannot last. An internationally acclaimed novel, already published in half a dozen countries, Good Morning Comrades is an unforgettable work of fiction.

Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret by Ondjaki (trans. Stephen Henighan)

By the beaches of Luanda, the Soviets are building a grand mausoleum in honour of the Comrade President. Granmas are whispering: houses, they say, will be dexploded, and everyone will have to leave. With the help of his friends Charlita and Pi (whom everyone calls 3.14), and with assistance from Dr. Rafael KnockKnock, the Comrade Gas Jockey, the amorous Gudafterov, crazy Sea Foam, and a ghost, our young hero must decide exactly how much trouble he’s willing to face to keep his Granma safe in Bishop’s Beach. Energetic and colourful, impish and playful, Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret is a charming coming-of-age story.

Transparent City by Ondjaki (trans. Stephen Henighan)

In a crumbling apartment block in the Angolan city of Luanda, families work, laugh, scheme, and get by. In the middle of it all is the melancholic Odonato, nostalgic for the country of his youth and searching for his lost son. As his hope drains away and as the city outside his doors changes beyond all recognition, Odonato’s flesh becomes transparent and his body increasingly weightless. A captivating blend of magical realism, scathing political satire, tender comedy, and literary experimentation, Transparent City offers a gripping and joyful portrait of urban Africa quite unlike any before yet published in English, and places Ondjaki, indisputably, among the continent’s most accomplished writers.

***

The Day-Breakers by Michael Fraser and UNMET by stephanie roberts, both designed by Ingrid Paulson.

Poetry

UNMET by stephanie roberts

Leaning deliberately on the imagined while scrutinizing reality and hoping for the as-yet-unseen, UNMET explores frustration, justice, and thwarted rescue from a perspective that is Black-Latinx, Canadian, immigrant, and female. Drawing on a wide range of poetics, from Wallace Stevens to Diane Seuss, roberts’s musically-driven narrative surrealism confronts such timely issues as police brutality, respectability politics, intimate partner violence, and ecological crisis, and considers the might-have-been alongside the what-could-be, negotiating with the past without losing hope for the future.

The Day-Breakers by Michael Fraser

“It is not wise to waste the life / Against a stubborn will. / Yet would we die as some have done. / Beating a way for the rising sun wrote Arna Bontemps. In The Day-Breakers, poet Michael Fraser imagines the selflessness of Black soldiers who fought for the Union during the American Civil War, of whom hundreds were African-Canadian, fighting for the freedom of their brethren and the dawning of a new day. Brilliantly capturing the rhythms of their voices and the era in which they lived and fought, Fraser’s The Day-Breakers is an homage to their sacrifice and an unforgettable act of reclamation: the restoration of a language, and a powerful new perspective on Black history and experience.

***

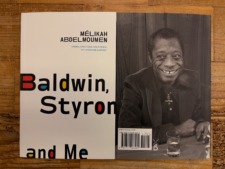

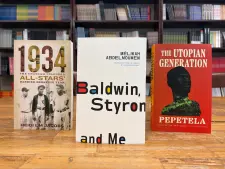

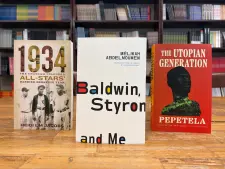

1934 by Heidi LM Jacobs, designed by Michel Vrana; Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc), designed by Ingrid Paulson; and The Utopian Generation by Pepetela (trans. David Brookshaw), designed by Zoe Norvell.

Other reads for Black History Month

1934: The Chatham Coloured All-Stars’ Barrier-Breaking Year by Heidi LM Jacobs

The pride of Chatham’s East End, the Coloured All-Stars broke the colour barrier in baseball more than a decade before Jackie Robinson did the same in the Major Leagues. Fielding a team of the best Black baseball players from across southwestern Ontario and Michigan, theirs is a story that could only have happened in this particular time and place: during the depths of the Great Depression, in a small industrial town a short distance from the American border, home to one of the most vibrant Black communities in Canada. Drawing heavily on scrapbooks, newspaper accounts, and oral histories from members of the team and their families, 1934: The Chatham Coloured All-Stars’ Barrier-Breaking Year shines a light on a largely overlooked chapter of Black baseball. But more than this, 1934 is the story of one group of men who fought for the respect that was too often denied them. Rich in detail, full of the sounds and textures of a time long past, 1934 introduces the All-Stars’ unforgettable players and captures their winning season, so that it almost feels like you’re sitting there in Stirling Park’s grandstands, cheering on the team from Chatham.

Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc)

In 1961, James Baldwin spent several months in William Styron’s guest house. The two wrote during the day, then spent evenings confiding in each other and talking about race in America. During one of those conversations, Baldwin is said to have convinced his friend to write, in first person, the story of the 1831 slave rebellion led by Nat Turner. The Confessions of Nat Turner was published to critical acclaim, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1968, and also creating outrage in part of the African American community.

Decades later, the controversy around cultural appropriation, identity, and the rights and responsibilities of the writer still resonates. In Baldwin, Styron, and Me, Mélikah Abdelmoumen considers the writers’ surprising yet vital friendship from her standpoint as a racialized woman torn by the often unidimensional versions of her identity put forth by today’s politics and media. Considering questions of identity, race, equity, and the often contentious public debates about these topics, Abdelmoumen works to create a space where the answers are found by first learning how to listen—even in disagreement.

The Utopian Generation by Pepetela (trans. David Brookshaw)

Lisbon 1961. Aware that the secret police are watching them, four young Angolans discuss their plans for a utopian homeland free from Portuguese rule. When war breaks out, they flee to France and must decide whether they will return home to join the fight. Two remain in exile and two return to Angola to become guerilla fighters, barely escaping capture over the course of the brutal fourteen-year war. Reunited in the capital of Luanda, the old friends face independence with their confidence shaken and struggle to build a new society free of the corruption and violence of colonial rule.

Pepetela, a former revolutionary guerilla fighter and Angolan government minister, is the author of more than twenty novels that have won prizes in Africa, Europe, and South America. The Utopian Generation is widely considered in the Portuguese-speaking world an essential novel of African decolonization—and is now available in English translation for the first time.

***

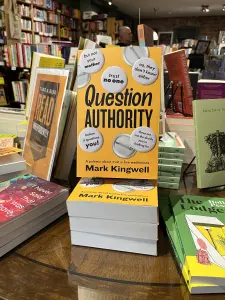

A Note on Question Authority by Mark Kingwell

Reader, if you’re like me, you’re probably trying to make sense, whether via the reading of entrails or essays, of the Trump and Musk train wreck and all it entails. Lest our American readers fear I’m throwing stones—and based on what we know of this substack, we have more American readers than Canadian ones—we are in the middle of something that may prove as worrisome here. (Please see last week’s Bibliophile for further insight.) Though we’ve been posting the Bibliophile on Substack for the better part of four months, I’ve only started personally using it in the last few days, devouring essays and insights by the likes of Anne Applebaum, Timothy Snyder, Paul Wells, David Moscrop, Nora Loreto, Paul Krugman, and many others: whatever else may separate these writers from one another, however they may differ on the root cause of what ails us, what they all seem to agree on is that we’re, on both sides of the 49th, in a whole mess of shit.

But despite the overwhelmingly varied offerings of Substack, not everything worth reading can be found here. When it comes to outlining the first causes for our current predicament, I still find that one of the best things I’ve read in recent memory comes via . . . a book. Mark Kingwell’s Question Authority: A Polemic About Trust in Five Meditations, which published in the US this past Tuesday, offers, for my money, one of the most intelligent analyses of what underpins our division and discord: we are, all of us, Kingwell argues, on the left and on the right, too often animated by an unshakeable belief in our personal righteousness and superiority, or what Kingwell calls doxaholism: an addiction to conviction.

Question Authority by Mark Kingwell (cover by Michel Vrana). Pictured here in Biblioasis Bookshop.

Evidence of this addiction is everywhere: around the family dinner table as much as in the partisan jibes of Trump or Trudeau or Poilievre: it makes real thought, conversation, and the trust essential to finding solutions to the real problems we face impossible. Our addiction to conviction undermines our faith in essential institutions and one another; it lubricates our descent into a range of defeating particularisms that make us even more vulnerable to manipulation. And there are those currently in power, or on the cusp of it, who’ve been very adept at this manipulation.

But this is not all that Kingwell offers: in addition to his diagnosis, he suggests an antidote, or at the very least the beginning of one, what he calls compassionate skepticism. Rather than retreating further into the particularisms of identity or grievance, Kingwell argues that we need to recentre ourselves with humility, into what he calls the ethical habit of “constructive disbelief governed by (an) awareness of our shared vulnerability.” If the past months have shown us anything, surely, it’s that we are all increasingly vulnerable, even if unequally so, to matters well outside our control: it’s in an acknowledgment of this truth that we’ll find strength.

Speaking of David Moscrop, he did an excellent interview with Mark for the Jacobin a couple of months ago about Mark’s new book: you can read it here. And find Mark’s book wherever it is you go for such things.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

***

In good publicity news: